Source from Dr. Aspen Chen 05/2019

Posted in 05/2019

========== English Version ==========

“Going to America”: An Overview on Taiwanese Migration to the US

Written by Aspen Chen

Image Credit: Untitled, by Ken Walton/Flickr, License: CC by 2.0

“Going to America” (“去美國”) is a familiar phrase in Taiwan. Many people have personally studied or worked in the United States. Even more, have relatives or friends who have done so. Indeed. The United States emerged as the top destination for Taiwanese out-migration throughout the second half of the twentieth century. It has remained so for long-term residence even when the number of Taiwanese people studying and working in China has increased substantially.

Just like Taiwan, plenty of countries have a sizable diaspora population in the United States, but most of them have apparent reasons behind their immigration patterns. In contrast, the large-scale Taiwanese migration to the US cannot be easily explained by any obvious factors: Taiwan is not geographically close to the US (compared to Mexico or countries in Central American and the Caribbean). Neither has it been part of the US territory (consider the Philippines). Taiwan is also not an English-speaking country (unlike India) and has no history of large-scale US military involvement (as in South Korea or Vietnam).

The ostensible dearth of strong geographic, cultural, or political ties between the two places make the large-scale out-migration of Taiwanese to the US an interesting phenomenon: Why do so many Taiwanese immigrate to the US, and how has the pattern changed over time?

Taiwanese Immigrant In the US: Size and Socioeconomic Status

Taiwanese immigrants in the United States are distinct in two ways: their size is substantial, and their socioeconomic status is remarkably high. According to the 2010 US Census, the 358,460 Taiwanese immigrants rank as the 23rd largest immigrant group. While this number does not seem exceptional, it becomes more remarkable once we consider the broader context. The number of Taiwanese immigrants is similar to those from larger countries such as Italy, Iran, and Brazil. Moreover, immigrant groups further up in the ranking are from countries either with much larger population sizes—such as China, India, or the Philippines—which are positioned closer geographically to the US (such as El Salvador, Cuba, or the Dominican Republic), or meet both conditions ( as Mexico does).

In terms of socioeconomic status, Taiwanese immigrants have notably high educational and income levels. Over 70% of Taiwanese immigrants hold a bachelor’s degree. This percentage is twice that of the general U.S. population and greater than all immigrant groups from Asia, which tends to be more highly educated, other than India. As far as income is concerned, the 2017 American Community Survey shows the household income of Taiwanese Americans (which includes both immigrants and the native-born) to be $99,257. This number ranked only below Indian Americans across all ethnic groups and far exceeded the median income of all US households at $60,336.

Explaining the Policy and Historical Context

What may explain the distinct size and socioeconomic status of Taiwanese immigrants? Answering this question requires understanding the policy and historical context in the United States, Taiwan, and the two connections.

Taiwanese migration to the United States did not begin until after World War II. During much of the 1910s and 1940s, the United States maintained a restrictive immigration regime, outlawing migration from much of Asia. Some anti-Asian restrictions were loosened after the United States joined the war and had to confront the paradox of banning subjects of China, which was its ally. After the war, the US Congress passed a series of bills to admit political refugees and asylum seekers were fleeing communist regimes. Some of the quotas were reserved for populations impacted by the Chinese Civil War. While the primary beneficiaries of these policies came from China and often transitioned through Hong Kong or Taiwan before landing in the United States, their movement set up the institutional and cultural foundation for Taiwanese migration to the US later.

In 1965, the US Congress instituted a new comprehensive immigration framework under the Hart-Celler Act. This new system shaped Taiwanese migration for decades to come in two important ways. First, Hart-Celler replaced the previous discriminative nationality quota system that had targeted immigrants from Asia and parts of Europe with an ostensibly similar system that admits 20,000 citizens from every nation each year. Even though Taiwanese migration was initially subject to the quota allocated for China, the cap had little deterring effect because population movement originating from Communist China was negligible. Moreover, this is because the United States continued to recognize the Republic of China regime, which had retreated to Taiwan, as the legitimate government of China. During this period, the number of Taiwan-born individuals who naturalized as US citizens every year were between a few thousand to slightly more than ten thousand. While the annual cap poised to be an issue after the United States recognized the People’s Republic in 1979, Taiwanese Americans successfully lobbied the US Congress to allocate another separate 20,000 slots for Taiwan under the Taiwan Relations Act.

Another significant change under Hart-Celler was establishing family reunion and employment as the two primary channels for immigration to the United States. The latter channel became particularly important for Taiwanese migration to the US. The first wave of Taiwanese immigrants arriving in the 1960s and 1970s most often started their journey as graduate students when the United States actively recruited high skill talent from abroad during the Cold War. Many of these students subsequently settled long-term through the employment immigration channel, and in turn, became able to sponsor their family members to move to the US. This mechanism largely shaped the high “selectivity” of Taiwanese migrants, which I will elaborate on below.

Apart from the changes in US immigration policies, the activities of US military, political and economic forces in Taiwan during the Cold War must not be discounted. As the world system theory suggests, the presence of political, economic or military forces from the “core” regions of the world (such as the United States) in the “peripheral” regions (such as Taiwan or other developing nations) often leads to close material and ideological links, which, in turn, can cause population movement to “core” regions. For example, decades of US military presence in South Korea have resulted in tens of thousands of cross-nation marriages. Various US institutions on the ground also promoted American culture to the South Korean public and shaped the aspiration to live in the United States. In the case of Taiwan, US forces and US aid that existed throughout the 1960s and 1970s projected soft power in the then poorer and authoritative Taiwanese society, leading many Taiwanese youths to aspire to study, work and live in the United States.

The High Selectivity of Taiwanese Migration to the United States

A common misconception in the United States based on the income and education levels of the Taiwanese immigrant population is that the general population in Taiwan is highly skilled and well-off. However, this overlooks the fact that the Taiwanese migration to the US is highly “selective.” In other words, Taiwanese who successfully emigrated tend to have more skills and resources than the general Taiwanese population. To illustrate, one study finds that, in 1980, 61% of the adult Taiwanese immigrant population in the US held at least a college degree even when the share of the general Taiwanese adult population at the time was only 5.4%.

While we have explained how US policies and historical involvement in Taiwan enabled and shaped the Taiwanese migration, we must also consider the conditions at both ends of the migration chain that led to this unusual high selectivity.

For one thing, Taiwan already had segments of educated populations prone to emigrate at the beginning of the Cold War. Prior to the comprehensive immigration reform of the 1965 Hart-Celler Act, most Asians still faced tight restriction in moving to the United States. An important exception at the time was through attending US colleges or universities. This option appealed to the many college-educated Chinese refugees who followed the Republic of China government to Taiwan. Indeed, making another move to the US likely meant both better life prospects and safety from the anticipated Communist incursion on the island. In addition, Japan had already instituted modern education in Taiwan during the last two decades of its colonial rule for the older Taiwanese population. Taiwanese youth from elite families or with academic potential also often studied in Japan. This combination of modern education and the precedents of studying abroad set up the academic qualification and cultural receptiveness for studying in the US. Furthermore, Suzanne Model’s research found that many Taiwanese college students in the Republic of China’s rule chose to study in the US earlier. This is because of political surveillance and censorship, dissatisfaction with the educational quality in Taiwan, and a labour market unfriendly to college graduates who lack special “connections.”

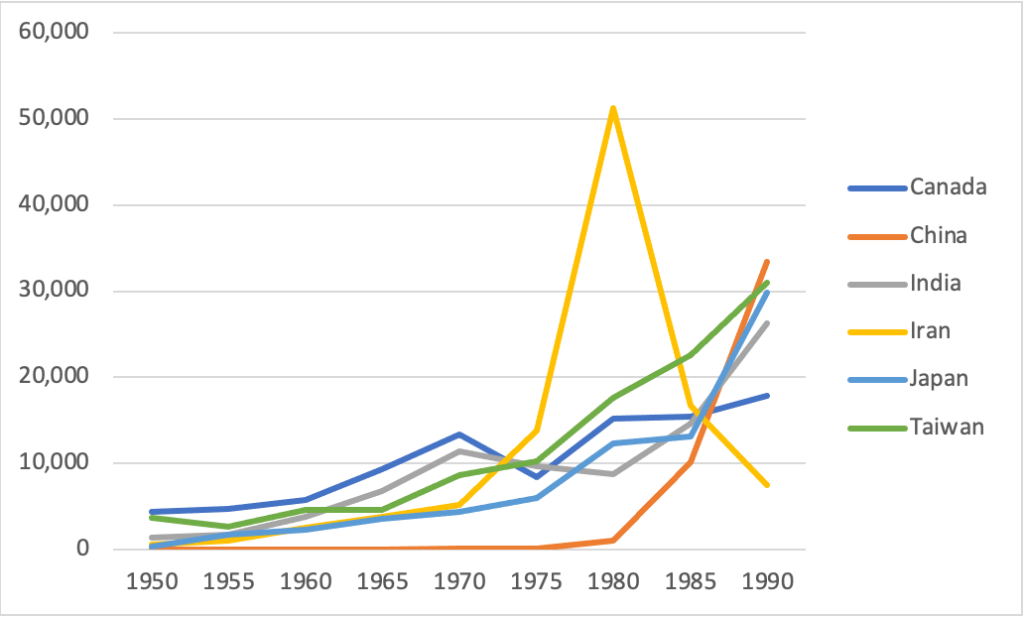

From a comparative perspective, the size of Taiwanese students in the United States was exceptionally high for decades. Figure 1 illustrates the number of international students in the United States from the top sending countries between 1950 to 1990. This figure shows that Taiwan was consistently among the top origins. This fact is even more remarkable considering other countries in this figure all have larger populations than Taiwan.

Figure 1. International students in the United States from top origins (1950-1990)

Data source: International Institute of Education

International students from Taiwan in the 1950s and 1960s often successfully transitioned into US immigrants. Many were able to find employers to sponsor their immigration process when the demand for skilled labour was high and employment restrictions for international students were few. However, some estimate suggests that 90% of Taiwanese students in the US in the 1950s and early 1960s did not return to Taiwan upon completing their degrees.

Governmental policies in Taiwan at the time also contributed to the high selectivity of the immigrants. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, the Republic of China government enacted strict population control to limit the exodus of workforce and capital. As a result, studying abroad was among the few admissible reasons to receive an exit visa. Still, the applicants were required to have graduated college, complete the mandatory military service (for men), secure admission letters from foreign educational institutions, and have a guarantor in Taiwan to ensure the applicants would behave politically “proper” when aboard. These exit control measures were probably most responsible for the high selectivity of the Taiwanese immigration population since they imposed a high cost and left fewer options for less-educated individuals to leave.

In addition to exit control, other politically motivated policies in Taiwan also inadvertently shaped the composition of Taiwanese immigrants in the US. For example, before the end of the martial law in 1987, the government in Taiwan routinely denied students and scholars aboard whom it deemed politically problematic return to Taiwan. This practice, often referred to as “the blacklist,” led to highly educated Taiwanese stranded in foreign countries, most often in the United States, thus contributing to the selectivity.

Aside from the earliest and most significant study-to-employment pathway, Taiwanese people also moved to the United States through other channels. A sizable share of Taiwanese medical professionals and graduates in Taiwan migrated to the United States in the 1960s and 1970s to meet the perceived labour shortage in health care. As Taiwan’s economy improved in the 1980s, more people moved across the Pacific to operate a business or place their young children in the US K-12 educational system. In addition, government research estimates that, between 1972 to 2000, the number of Taiwanese individuals who immigrated to the United States through family sponsorship (either as a spouse, child, parent, or sibling) is twice that of those through the employment channel. In all these circumstances, the immigrants still tend to be highly selective given their high levels of education (in the case of medical professionals) or ample economic resources (in the case of business operation). Because educational levels tend to be similar between family members (otherwise known as educational homophily or homogamy), even the family reunion route still maintained the selectivity of Taiwanese immigrants.

Deceleration of Taiwanese Migration to the US

The rate of Taiwanese migration to the United States reached its peak in the late 1970s and the 1980s. It then began to slow down in the mid-1990s under both the employment-based and family-sponsored channels. Even the number of Taiwanese students studying in the United States plateaued around this time, as shown in figure 2, which tracks the sizes of international students in five major sending countries from Asia. In recent decades, China, India, and South Korea have all consistently overtaken Taiwan in the sizes of their student populations studying in the US.

Figure 2. International students in the US from selective countries (1950-2015)

Data source: International Institute of Education

The stagnation of the Taiwanese immigrant and student populations in the US has become a subject of interest in communities across both sides of the Pacific. The sober take in Taiwan interprets this change as indicative of a less ambitious generation and warns of declined global competitiveness. These changes have also raised concerns about the retention of the cultural identity for the Taiwanese American community.

However, from the standpoint of immigration research, this deceleration may reflect a maturation pattern in population movement. Similar patterns have already been observed for European, Korean, and Mexican migration to the US. All of these sending societies had experienced high emigration rates for extended periods during which large shares of their populations experienced poverty, violence, or political oppression. But once the political, economic and social conditions improved in the sending societies, their emigration rates abated.

By the same token, the deceleration of Taiwanese migration to the US likely reflects structural progress in Taiwan. The high rates of out-migration from Taiwan to the US in the 1960s through the 1980s was driven by considerably disparities between the two societies. In addition to the apparent gap in living standards and economic opportunities, Taiwan was also under the rule of an authoritative regime that denied constitutional rights to its citizens and prosecuted perceived political dissidents. Moreover, the imminent threat of war and political isolation from the international community weighed heavily on the minds of many. Most of these conditions were relieved around the time out-migration from Taiwan to the US slowed. Furthermore, Taiwan’s higher education expansion in the 1990s and the rise of non-U.S. destinations have offered many new alternatives for people who liked to pursue advanced studies.

Comparing Taiwan and South Korea, two societies with similar historical trajectories after World War II should provide further insight into the distinct nature of Taiwanese migration to the United States. Figure 3 compiles the changes in the annual rate of naturalization for immigrants from South Korea and Taiwan between 1956 and 1987. The lines for the two countries tracked similarly in the first decade when Asian migration to the US was complex. Nevertheless, the rate of naturalization for South Koreans picked up rapidly after the 1965 Hart-Celler Act had created the comprehensive immigration framework. Their rate growth soon exceeded the annual 20,000 slots, which is possible since the immigration of close family members is not governed by the cap.

In contrast, Taiwan’s annual rate of naturalization never reached the cap. This disparity is too great even when the differences in population size are accounted for. More likely, it suggests that the push forces in Taiwan were never as strong as it was in South Korea. The differences in push forces are not hard to imagine once we consider the historical context. The Korean War, more widespread poverty, and a more ruthless authoritative regime generated a more intense push for out-migration for South Koreans. This perhaps explains why many Korean immigrants in the US hold college degrees but settle for low-skilled jobs such as operating vegetable stand or bodegas: leaving South Korea was likely more important than maximizing one’s employment potential. This type of overqualification is less often found among the highly educated Taiwanese immigrants in the US. We can confidently infer those Taiwanese immigrants tend to be much more self-selective so that only those with better chances of succeeding moved and stayed in the US.

Figure 3. Annual size of naturalized population (1956-1987).

Data source: Long and Huang (2002); Min (2011)

Epilogue: Some Personal Notes on the State of Taiwanese Migration

Anecdotally, I personally have observed some of the changes that I have just discussed through community organizing in the United States over the last few years. The older generation of Taiwanese Americans do appear to be highly selective in their education, almost uniformly graduating from the small number of colleges and universities in Taiwan at the time and coming to the US to study or be with their family. They came at a time when Taiwan’s material and political conditions significantly trailed the United States, and when “going to America” meant a golden ticket to better lives. Most had never travelled abroad or even been on an airplane prior to coming to the US, and many told stories of cultural shock upon their arrival. On the other hand, they encountered a more friendly immigration regime (at least after 1965) and a more receptive labour market than many new immigrants face today. Their generation usually stayed in the US after completing school through employment or family reunion channels.

In contrast, Taiwanese visitors and immigrants today are much more diverse in their background, career trajectories, and future plans. There are still plenty of Taiwanese students in US colleges and universities, but they have a wide range of plans after graduation. While some still intend to try out the US labour market, others are content to return to Taiwan, expecting to find reasonable work conditions and compensation back home. Some students are open to working in other places, including even developing countries. Obviously, part of their calculation is driven by Taiwan’s improved working and living conditions and a more dynamic global economy. However, it is also true that securing employer sponsorship to settle in the United States is more complicated than it was for earlier generations of Taiwanese immigrants.

In the meanwhile, more Taiwanese have been arriving in the US for reasons other than studying. Short-term academic or professional exchanges have become more common between the two places. With Chinese language education on the rise in the United States, some Taiwanese now teach Chinese courses. Another type of Taiwanese migration to the US is work-based relocation. As Taiwan and its population become more embedded in the global economy, Taiwanese employees of multinational corporations are increasingly likely to be moved to branches or units in the United States (or other countries). In contrast to early waves of Taiwanese arrivals, those relocated for work today sometimes do not have formal US educational experiences or plan to stay long-term. While some eventually decide to reside in the US, this option has become only one of many career possibilities.

What may hold for the future of Taiwanese migration to the United States? Taiwan’s improved conditions and integration into the international world have shaped today’s more tempered and diversified migration pattern. Still, a few factors have the potential to bring about substantial changes to this population movement. Most apparently, a low birth rate in Taiwan means a smaller young cohort for potential out-migration. The shrinking demographic has already threatened Taiwan’s higher education enrolment and should impact Taiwan’s pipeline for sending students abroad. Changes in the United States also have the potential to reshape the migration flow in different ways. Adverse conditions can deter movement to the US and even prompt some reverse migration. For example, the covid-19 pandemic not only reduced the arrival of foreigners (including international students) in the United States throughout 2020 and early 2021, but some Taiwanese immigrants also even returned to Taiwan with their children when many US schools turned to remote learning. The rise of anti-Asian or anti-immigrant sentiment can also generate a cold climate or prompt new immigration policies that discourage immigration, including those from Taiwan. On the other hand, improved diplomatic and economic relations between Taiwan and the United States may spur more interpersonal movement or even favourable immigration measures.

Similarly, other conditions in Taiwan must also not be discounted. For example, the low cost of living and health care relative to the United States has long been an essential factor driving the reverse migration of Taiwanese seniors in the United States. In contrast, interests in moving to the United States appeared to have spiked at the time of this writing due to the coronavirus outbreak in Taiwan. And obviously, the recent development in Hong Kong reminds us not to overlook the possibility of significant exodus should China’s threat to Taiwan become more imminent. To conclude, I believe the shifts in migration patterns that I discussed in this piece reflect the maturation of Taiwanese migration to the US. The political, economic and social conditions in Taiwan during the beginning of the Cold War prompted the most educated segment of the population to move to the US in large numbers and created an unusually selective immigrant population. With the general condition in Taiwan improving over the decades, however, the push forces in Taiwan for large scale out-migration have subsided. “Going to America” was once about a highly coveted and meaningful step in Taiwanese society. Today, it is increasingly just one of the many possible options for Taiwanese people.

Aspen Chen teaches Sociology at North Hennepin Community College, Minnesota, USA

This article was published as part of a series on Taiwanese Americans.

– Source: original post

– Last updated on: 06/25/2021