The Role of Taiwanese Students in the Early Years of the Taiwanese Independence Movement at University of Wisconsin (1960~1970)

Author: Suy-Ming Sam Chou

Editor: Mei Fun Tsai

1. Introduction

Broadly speaking, the majority of the associations and organizations in the United States that were involved in the overseas Taiwanese movement were composed of Taiwanese study-abroad students. The early wave of Taiwanese students who came to the United States (1956-1966) witnessed the Kuomintang’s corruption and incompetency, and they experienced the withering of the Taiwanese economy after the Second World War. Especially after the occurrences of the 228 Incident, a lot of people, feeling threatened by the National Security Bureau, retreated from politics and decided to keep silent. Before they went abroad, many were instructed by their families to avoid participating in political organizations or activities. But, at that time, most Taiwanese students struggled financially, tended to have more reserved and introverted personalities, and weren’t very confident in their English skills (because learning English had been prohibited during the war). Thus, students were naturally very happy to meet others from their homeland, and they easily became very close with their friends and comrades. Thus, Taiwanese student associations were formed to fill the needs of the community.

Of course, the formation of social groups was also related to the environment. Take the city of Madison, a major U.S. city and the capital of Wisconsin, as an example. In the 1960s, the population of Madison was just under 100,000 people (currently around 200,000), and with 40,000 students at UW-Madison, it was one of the largest state universities in the United States. The campus is also well-known for its beauty. The demographic breakdown of Madison was quite unique: 30% of German descent, 15% of Irish descent, 12% of Norwegian descent, 10% of British descent, 6% of African descent, 5% of Polish descent, 4% of Italian Descent, and 3% of Asian descent (Taiwanese, South Korean, Japanese, Indian); it is an international city. When Madison residents saw foreigners, they always asked where they came from. In the 50s and 60s, there were some Taiwanese students who felt uncomfortable when they were asked this question. Only a minority of people easily asserted that they were “Chinese,” while the majority of people, after seriously and consciously contemplating their national identity, had an identity crisis. Only after undergoing such psychological distress, could people reach a clearer sense of national identity and affirm their own nationality. The environment of such a unique and international city like Madison encouraged students to consciously identify with their homeland and take pride in their roots. Thus, many Taiwanese students stopped identifying with the name “Republic of China.”

Additionally, since a group of biochemistry students from the National Taiwan University’s Medical School had previously come to Madison and paved the way for others, the city was quite well-known. In 1949, the Ministry of Education selected and sent Professor Ta-cheng Tung to the University of Wisconsin to conduct research at the Biochemistry department’s Enzyme Research Institute for two years. This established a long-term research exchange system, which allowed biochemical researchers from NTU’s medical school to continue to study at the University of Wisconsin. NTU medical school professors Kuo-huang Lin, Shan-ching Sung, Ya-pin Li, Po-chao Huang, and Chen-chung Yang have all studied at the University of Wisconsin.

In 1958, after working as a teaching assistant in the NTU Department of Biochemistry for two years, Dr. Grace Wu Chou came to conduct research at the University of Wisconsin, following the recommendation of professor Ta-cheng Tung. In the summer of 1959, her fiancé, Dr. Suy-Ming Sam Chou, came to Madison after finishing his military service, and the two were married at the end of 1959. After that, the two were extremely busy because they were simultaneously working and studying for their PhDs, but since they were the only married couple on campus, their house became a meeting place for international students who identified as Taiwanese. Every weekend, they would gather together to sing Taiwanese songs, eat Taiwanese food, speak Taiwanese, talk about their hometowns, and exchange opinions and solutions. Thanks to the warmth of the Chou family’s home, these wanderers were able to ease some of their loneliness.

2. The Official Registration of the University of Wisconsin Formosan Club (UWFC), October 19th, 1963.

The Zhous gave birth to three sons, one after another, and the Taiwanese students were starting to need a larger meeting place. They also began to discuss creating a Taiwanese association or student club under which they could rent campus spaces to use. In the beginning of 1963, they registered under the name “UW Formosan Student Club.” News of this quickly spread to the Republic of China’s embassy in Washington D.C., who ordered the Kuomintang students at the University of Wisconsin to block the club’s creation on the grounds that such a student association already existed on campus (the Chinese Students Association led by Kuomintang students). After Taiwanese students protested multiple times, the school decided to let the two groups openly debate the issue in the Student Senate. The Taiwanese students sent Teng-chun Li, the most fluent English speaker, to represent them at the debate. Using beautiful and fluent English, he explained the origin of the name of “Formosa,” as well as the fact that its history and geography are very different from China. He also emphasized the etymology of the name “Taiwan,” which came from a word in the language of the Plains Indigenous people of Anping, Tainan. His speech was extremely moving, and the Student Senate decided to recognize that the difference in cultural and historical backgrounds between Taiwan and China are similar to the differences between the United States and Britain. Thus, it accepted the application for the Formosan Club.

In accordance with school regulations, the Formosan Club completed its charter on October 2nd, 1963 (the membership fee was $1 per semester), and selected a professor to act as their adviser (Dr. Suy-Ming Chou happened to meet the requirement for this, so he took on the responsibility). On October 19th, they went to the Student Center to officially register “The Formosan Club of the University of Wisconsin.” After this, the majority of the club’s activities were held at the Student Center, and once in a while, they used the baseball field to relieve some of the political pressure they were facing from the Kuomintang students.

Wanting to share their success, the UW Formosan Club sent Hung-mao Tien to Manhattan, Kansas to share the benefits of registering a club with their school and encourage them to apply to register as well.

Since the reasons for meeting were different each time, and moreover, the organization charter stated that the Formosan Club was a non-political organization, they had no option but to form a separate political organization. Thus, University of Wisconsin’s second Taiwanese student organization was born.

On February 29th, 1964, prior to the formation of the second organization, Suy-Ming Chou and his wife took their three young children, driving for over 20 hours through ice and snow, to the Kuomintang embassy in Washington D.C. to participate in protests held by the United Formosans for Independence, commemorating the 17th anniversary of the 228 Incident. Before this, Suy-Ming Chou and his wife had their passports revoked, making them undocumented and nationless. Twice, in June of 1963 and January of 1968, they had nearly been deported, forced to live without any sense of stability for over ten years.

3. The Formosan Affair Study Group, April 1964

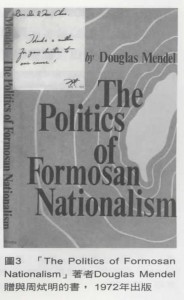

Half a year after the establishment of the Formosan Club, though all the Madison Taiwanese students identified as “Taiwanese,” they decided to separate the political and non-political activities. Those with a strong political consciousness decided to form another group to discuss American and Taiwanese political issues. This group was created by Teng-chun Li, Chi-ming Huang, and Hung-mao Tien, who at the time, were all doctorate students in the Department of Political Science. Teng-chun Li drafted the charter and invited Dr. Suy-Ming Chou to act as faculty adviser. They also invited Douglas Mendel, a professor of Political Science at UW Milwaukee and a behind-the-scenes support of the organization, to join as an honorary member.

At the time, Professor Mendel was writing “The Politics of Formosan Nationalism” and had asked his research assistants Teng-chun Li and Chi-ming Huang to translate it into Japanese, and Hung-mao Tien to translate it into Chinese. Professor Mendel lived in Taiwan in 1957, 1961-1962, and 1964. He’d interviewed nearly 1,000 students, businessmen, and commoners, and contacted Taiwanese people living in Japan and the United States. This book concluded his opinions and the results of his research on Taiwan. He properly awakened the Taiwanese people’s consciences and their sense of dignity, giving Taiwanese students the unparalleled courage needed to express their desire to identify as Taiwanese.

Nonetheless, under the watchful eyes of the Kuomintang students and the threat of random reporting, only 10 members, including Suy-Ming Chou, dared to publicly participate in the group. Thus, a year after its establishment, the group was still not registered with the school. Later, the “national flag incident” boosted morale and the group officially registered with the school on June 19th, 1965, becoming the school’s second Taiwanese student organization.

In addition to publishing Formosan Forum, the Formosan Affair Study Group invited professors of Political Science from the University of Wisconsin, like Mendel, Carlish, and Tan to come and participate in their regular symposiums on Taiwanese issues. Together they discussed the history, economy, and politics of Taiwan, as well as the impact of the Vietnam War on different Southeast Asian countries. Though the FASG only ran for 3 years, its existence spawned two historical events, which helped strengthen the overall unity of the overseas Taiwanese community. The first was the “national flag incident,” and the other, the “Formosa Leadership United Congress.”

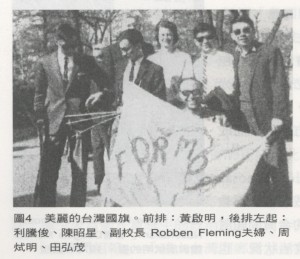

4. The Appearance of the Taiwanese Flag in the University of Wisconsin Flag Parade on May 2nd, 1965

In 1965, to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the United Nations’ founding, Vice-president of the University of Wisconsin, Robben Fleming, sent a notice to all of the international student associations, inviting them to bring their country’s flag to participate in the International Day Flag Parade. The members of the University of Wisconsin Formosan Club and the FASG agreed that they should use this opportunity to express the wishes of the Taiwanese people and demand democracy, freedom, and independence for the Taiwanese people. This was because FASG’s mission included “promoting the establishment of a free and democratic society in Taiwan” and “Taiwanese self-determination.” But, no one felt that the flag of the Republic of China, which is actually the Kuomintang Party’s flag, accurately represented Taiwan. After discussing, they decided to make their own symbolic Taiwanese flag. They used ocean blue for the background, representing the surrounding ocean, and depicted the island and the Penghu archipelago in white, symbolizing peace. It was also embellished with the 7 large letters that spelled out FORMOSA in an eye-catching gold color. Dr. Grace Chou spent a lot of time designing and sewing a large flag, and also made several smaller flags.

On May 1st, student representatives from many different countries gathered at the Student Center and were arranged in alphabetical order. When they called China, Chinese student representatives from Taiwan placed the Republic of China’s flag over the island of Taiwan on the world map. When Taiwan was called, an FASG member moved the flag of the Republic of China onto the Chinese mainland and shouted, “successful counterattack on the mainland?” before sticking a small Taiwanese flag on the island of Taiwan. Because of the suddenness of the event, the Chinese student representative was caught off-guard, and could not respond when he heard the words “successful counterattack on the mainland.”

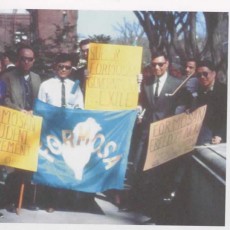

The second day, on May 2nd, Taiwanese students participated in the International Day Flag Parade, waving their beautiful and splendid Taiwanese flag. It was a very eye-catching flag, comparable to the French flag that was being flown beside it. The parade began at the bronze statue of President Lincoln, the “Father of Democracy,” on Bascom Hill (Image 5). Army, Navy, and Airforce troops, carrying the American flag and the flag of the United Nations, led the parade group downhill towards the Wisconsin Capitol Building, through Park Street, left to the Student Center, and back up the hill. The entire journey took a total of 50 minutes. Dr. Suy-Ming Chou was chosen to be in charge of holding the banner (Image 7). The Taiwanese Flag that was hand-sewn by Dr. Grace Chou fluttered in the wind of Bascom Hill, announcing to the entire world that in the east there was a country called Formosa, a beautiful island whose islanders hoped to establish a free, democratic, and independent country.

Vice-president Robben Fleming and his wife also attended the ceremony. When he realized that Dr. Suy-Ming Chou, who was excitedly and proudly waving his national flag, was a member of the school faculty, he was extremely happy and kind. He sincerely asked about various Taiwan-related issues, and Dr. Chou explained them in detail one-by-one. The most frequently asked question from other audience members was: “what does ‘Formosa’ mean? (Why not ‘Taiwan’?)” The members of FASG used the theory presented in Professor Mendel’s book to explain: “The term “Formosa” means Beautiful Island, which is more commonly used among Westerners. The Taiwanese prefer not to use the word “Taiwan” because of their history of being suppressed by the Japanese before the second World War, and the Chinese after it. Of course, they were even more opposed to the name “Republic of China.” After the parade ended, Fleming and his wife took a group picture with the Formosan Club (Image 8). The greatest outcome of their participation in this parade was that they were able to convey the wishes of the Taiwanese people to the citizens of Madison and the Fleming couple.

Vice-president Robben Fleming is a very famous educator. After serving two years as Vice-president at the University of Wisconsin, he served as President of the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor for 12 years. Even after he retired in 1988, he was asked to serve as interim President of the University of Michigan, which is evidence of his good reputation.

When the “Chi-ming Huang Incident” occurred, an event which will soon be described in detail, he offered very comprehensive help to the Taiwanese students, a kindness that can never be forgotten.

5. Holding the Formosa Leadership United Congress (FLUC) October 29th-30th, 1965

The success of the “national flag incident” was very inspirational to the members of the the Formosan Affair Study Group. So, aside from completing their school registration which had been delayed for an entire year, everyone also began to participate more openly and enthusiastically in the Taiwanese Independence Movement, without fear of being secretly surveilled. However, at this time some bad news came from Japan: Thomas Liao, who had led the Republic of Taiwan Provisional Government for 18 years from Japan and was a prominent symbol of the overseas Taiwanese Independence Movement, had returned to Taiwan to surrender. The members of FASG had once made posters for the International Day Flag parade to express their support for the Provisional Government. But now, everyone felt more urgently than ever that overseas Taiwanese needed to unite and stay together. Thus, they invited all the Taiwanese organizations around the United States, especially the more politically-focused groups, to come to Madison to hold a conference. Though it was originally only intended to be a conference for Taiwanese students in the U.S., the response was so enthusiastic that the invitation was expanded to include organizations from Canada and Japan.

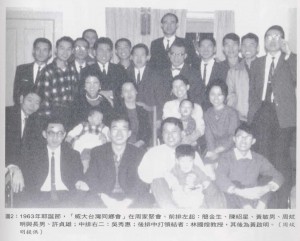

The attendees who participated in the event on October 29th and 30th, 1965, included: Man-li Kin from Tokyo’s Taiwan Youth Society (Birei Kin’s younger sister), Ming-an Chou from the Provisional Government’s Department of Foreign Affairs, I-ming Huang from Canada’s Taiwanese Human Rights Commission, President Edward Chen of America’s United Formosans for Independence, Mao-te Tseng of the Taiwanese Reading Association of New York, Chin-te Lai of the Minnesota Taiwanese Association, Hung-mo Hung of the Kansas Taiwanese Association, Pi-chao Chen of the New Jersey Taiwanese Association, Sin-I Hsiao of the Boston Taiwanese Association, and Wen-cheng Ke from Philadelphia (Edward Chen’s bodyguard). The participants from the University of Wisconsin included: Chao-hsing Chen, Teng-chun Li, Chen-hsiung Hsu, Sung-ling Lai, Jin-Sheng Jian, Chi-ming Huang, Chien-I Lin, Hung-mao Tien, Ming-shui Hung, Douglas Mendel Jr., and Suy-Ming Chou.

To prevent infiltration by Kuomintang agents, the conference adopted a number of confidential measures, such as: not announcing the meeting venue ahead of time and asking the participants to sign an affidavit in English and Chinese. They believed it was foolproof, but to their surprise, it was later discovered that Edward Chen’s bodyguard, Wen-cheng Ke, was actually one of the Kuomintang’s undercover agents.

As the chairman of the FASG, Suy-Ming Chou delivered the opening speech. He explained that “everyone who has made it their collective goal to fight for Taiwan’s independence must unite. Only after we come to a consensus, will we be able to establish an effective Taiwanese Independence Movement. . . . Don’t think that the Thomas Liao Incident is the end of the road for the Taiwanese Independence Movement. On the contrary, this incident should be able to bring a new dawn and new opportunities to the overseas Taiwanese Independence Movement. . . . The two topics that this conference can feasibly address are: (1) establishing a new Taiwanese political organization, and (2) publicizing the Taiwanese issue on the international stage.” These two topics were separated and presided over by Edward Chen and I-ming Huang respectively.

The hope behind the Formosa Leadership United Congress was that the FASG and UFI could “cast bricks to attract jade” (a Chinese idiom: to share ideas, in hopes of coming across a better idea), to help encourage more involvement in the Taiwanese Independence Movement. Prior to the United Congress, it was difficult to meet; initially, FASG proposed a jointly-hosted FASG and UFI conference, but UFI rejected this idea. There continued to be many disputes between the two groups during the conference, but they were finally able to reach a consensus: (1) FASG and UFI agreed to merge into a singular organization, (2) they collectively drafted the United Congress’ concluding remarks and public announcement, (3) they agreed to hold the second United Congress in Philadelphia within the next year. The newly formed organization’s name, as well as who would be responsible for its finances and publications, were details that had yet to be decided.

On the second day, Professor Mendel gave a special speech called “Formosan Nationalism.” After the conclusion of the United Congress, Presidents Suy-Ming Chou and Edward Chen, published a joint announcement on behalf of FASG and UFI. They called on all Taiwanese in the United States to join together to establish a collaborative organization and encouraged the members of the Taiwanese Independence Movement in Japan to start anew and cooperate with them. A total of 21 individuals participated in this event, including the smart, capable, enthusiastic, and proactive Teng-chun Li, Jin-Sheng Jian, and Chi-ming Huang, who all contributed greatly to this conference, and who have all passed away now. Hung-mao Tien and Pi-chao Chen later served as Taiwan’s Minister of Foreign Affairs and Deputy Minister of National Defense, respectively. Those who were unable to attend that day, but still expressed their thoughts and opinions via letters include: Po-shan Chen and Ren-shou Chen from New York, Tsai-ying Cheng from New Jersey, Tzutsai Cheng from Maryland, C. C. Yang from Kansas, Ching-Chin Chen from Illinois, Shao-chi Chen from Seattle, and Chiu-Sen Wang from California. Though not many people were able to attend, these passionate and ambitious Taiwanese were at least able to get to know one another and build the foundations for future cooperation.

October 30th marked the conclusion of the United Congress, and all of the participants took a group photo together. For safety reasons, they decided that Tseng Mao-te should keep the undeveloped film, the reason for which will become relevant after discussing the threat of the White Terror. Recently, Suy-Ming Chou met with Tseng Mao-te in Houston, who told him that the film was put in a bank safe for safekeeping. Later, he discovered that the bank had gone bankrupt and closed, but it was too late to retrieve the film.

6. The Establishment of the United Formosans in America for Independence, July 4th, 1966

During the Formosa Leadership United Congress, the largest source of conflict preventing agreement between UFI and FASG was that UFI wanted the newly formed organization to take on UFI’s debt. The second preparatory meeting, originally scheduled to be held in Philadelphia on January 1st and 2nd, was cancelled.

Months of difficult negotiations and complicated communications passed until Koo Kwang-ming of the Japanese Taiwan Youth Society accepted an invitation to visit a Taiwanese Independence organization in Los Angeles. During his visit, he was asked to help coordinate the merge. He had previously talked to representatives from both sides in Philadelphia and Madison, and also met with Tron-rong Tsai, Chiu-Sen Wang, and others in Los Angeles. Finally, representatives from both UFI and FASG agreed to hold discussions again in Philadelphia on June 18th, 1966. Apart from UFI’s Edward Chen, Fu-Chen Lo, Powen Wang, and James Chin-Chun Su; as well as FASG’s Su-Ming Chou, Teng-chun Li, Jin-Sheng Jian, Hung-mao Tien, Chen-hsiung Hsu, Kuei-hsiung Wang, and Chao-hsing Chen, representatives from 9 different regions were also invited to attend, including: Liang-Shing Fan, C. C. Yang, Michael S. K. Chen, and Strong Chuang from Kansas; Ron Chen, Tan-Sun Mark Chen, and Ren-chi Wang from Oklahoma; George Chang and Ming Cheng Liau of Houston; Sin-I Hsiao from Boston; Tzutsai Chen from Baltimore; Chin-te Lai from Minnesota; Tron-rong Tsai, Chiu-Sen Wang, and Frank Lai from Los Angeles. They resolved to establish the United Formosans in America for Independence (UFAI) on July 4th, 1966. All of the members had to sign an affidavit, and aside from the leaders of the group, the names of all of the other members of the group were kept secret.

Since the basic structure of this joint organization had been formed during the Formosa Leadership United Congress, many of the key figures had been participants in the conference. During the meeting, they elected Edward Chen as the Chairman to manage their joint affairs, and Suy-Ming Chou was elected as the Chairman of the Central Committee. Moreover, they decided that the organization would focus on the grassroots movement (by establishing Taiwanese associations in as many places as possible to discover leaders and encourage greater involvement in the mass movement) and enlightenment (by working on enlightenment through education, in order to raise the American public’s awareness and understanding of Taiwan). Four major goals were established:

- Advertise the Taiwanese people’s pursuit of democracy, freedom, and independence

- Establish the organization’s headquarters in New York, and encourage members to try and find work near New York after they graduate

- “The Long March to Freedom”: send members to tour universities and promote the concept of independence for Taiwan

- Publish and distribute a publication titled Formosagram

The biggest difference between UFAI and FASG was that the members of the former organization were scattered across the United States. The vast majority of UFAI’s members didn’t know each other personally, which made it difficult to communicate and organize meetings. The latter was a University of Wisconsin organization, so all the members could regularly meet and discuss, making it easy to divide the work and cooperate. Moreover, since FASG was an officially registered school organization, as long as it conformed with its charter and the school’s regulations, even its political conferences and public protests would be protected by the school. Conversely, UFAI was a political organization that was not affiliated with a university, so all of its activities had to be carried out within the boundaries of U.S. law, and they could be restricted by the Foreign Agent Registration Act. In other words, if UFAI collaborated with political organizations in Japan or Canada, or accepted foreign financial support, the members’ names, addresses, telephone numbers, as well as the entire organization’s political contributions and income would need to be registered with the Department of Justice. These regulations were based on concerns about the United States’ national security. Finally, the organization decided that if it became necessary, they would register the group under Chairman Edward Chen and Central Committee Chairman Suy-Ming Chou’s names.

After UFAI was established, the number of members gradually increased. In addition to the regular publication of Formosagram, the foreign affairs, organizational, research development, and overseas liason departments were all running smoothly. But there was only a small increase in donations, meaning that the annual budget was only $4,000. The organization’s expenses included the travel costs for the “Long March to Freedom” tour to American universities and the cost of advertising in The New York Times. After a year, the organization spent over $9,000, but it was able to accomplish a lot of very important foundational work. For example, George Chang and Ron Chen were sent on the “Long March to Freedom” tour, traveling from the East Coast to the West Coast to tour all the college towns that had Taiwanese students. They distributed copies of Taiwan Youth and Formosagram to university campuses, carrying out the work of ideological enlightenment, advocating Taiwanese consciousness, spreading the concept of building an independent nation, discovering individuals with the potential to leader the Taiwanese Independence Movement, and finding financial backers. Fu-Chen Lo, Jin-Sheng Jian, and Teng-chun Li started from Philadelphia and traveled northeast to visit schools in New England. In total, the “Long March to Freedom” tour visited a total of 30 different college towns, drove over 10,000 miles, recruited many Taiwanese student groups and organizations, and attracted the attention of many incredible allies, such as Harvard’s Fu-Mei Chang, as well as Yale’s Lung-Chi Chen and Tung-pi Chen.

But, before a year had passed, Chairman Edward Chen suddenly resigned in May of 1967. He resigned because Ron Chen of the Executive Committee felt that the only feasible route to Taiwanese independence involved the mobilization of the masses on the island. He felt that the UFAI’s policy of publicizing the issue on the international stage would not be effective. Since Ron Chen and Edward Chen’s theoretical policies were so vastly different, Edward Chen decided to step down from his position as Chairman. When this happened, Suy-Ming Chou and three other Central Committee members, Fu-Chen Lo, Ren-chi Wang, and Tung-yao Tsai, held an emergency meeting. Considering that this news might affect the morale of members in the organization, they decided to temporarily hold off from announcing the news and to hold elections for a new Chairman and Cabinet at the end of June.

7. Chi-ming Huang Incident, September 2nd, 1966

In 1964, Chi-ming Huang transferred from the East Asia Research Institute at Harvard University to a doctorate program at the University of Wisconsin’s School of Education. In March of 1966, he returned to Taiwan to collect data for his dissertation, “Taiwan’s Education System during the Era of Japanese Occupation,” a research project funded by a U.S. federal government education grant. Before his trip, he asked the opinions of many fellow Taiwanese people, and most of them opposed the trip out of concern for his safety. Professor Mendel and Suy-Ming Chou also felt that it would not be a good idea. Sure enough, on March 4th, 1967, The New York Times reported that Chi-ming Huang, a Taiwanese student studying aboard in the United States, had been arrested on September 2nd, 1966. He was accused of participating in the Taiwanese Independence United Congress in Chicago, and meeting with Japanese leaders of the Taiwanese Independence Movement when he had passed through Japan. He was prosecuted as a rebel in a military tribunal. On May 2nd, 1967, he was sentenced to five years in prison after a short and secret 2-hour trial, without being allowed to hear the indictment or consult a defense lawyer. Though he applied for an appeal, his application was rejected.

Chi-ming Huang wrote a letter to Suy-Ming Chou from prison, asking for his help. In his letter, he wrote that Edward Chen’s bodyguard, Wen-cheng Ke, and Hsien-ming Chang of the University of Wisconsin’s Chinese departments were secret agents and had been writing reports. He asked that the people of UW help him seek vengeance. When Suy-Ming Chou received this letter of distress, transmitted confidentially via New York Times reporter Fred Andrew, he immediately contacted the Vice-president of the University of Wisconsin, who was extremely shocked and sympathetic. Not long afterwards, thanks to his immediate help in contacting a number of different people, the President of the University of Wisconsin, Mr. Harrington, wrote a letter to the Secretary of State, Dean Rusk, asking him to intervene. President Harrington stated that he believed that since FASG was a legal and officially registered university organization, that had a faculty member serving as a consultant, it was the kind of organization that should have the freedom to debate political policies. The school could also guarantee that the organization had no intent of committing treason, nor was there any possibility of conspiracy. He also emphasized that a campus that promoted free speech could not tolerate the obstruction of legitimate academic research due to political pressures. Additionally, he threatened that if students from the Republic of China were not allowed to freely participate in American academic discussions, the University of Wisconsin would refuse to accept students from Taiwan, and they would encourage other universities to follow suit. Since President Harrington was also the President of the State University Federation for Agricultural Development, he also had a considerable amount of influence over other schools.

Suy-Ming Chou also sent a letter to I-ming Huang of the Canadian Human Rights Commission, asking him to help request assistance from the London-based organization, Amnesty International. Under strong pressure from the American academic community, the Nationalist Government reviewed Chi-ming Huang’s case on May 17th, 1967. On July 7th, they released him on the basis of having inadequate evidence, and on August 26th, after his release, Chi-ming Huang wrote a thank you letter to Suy-Ming Chou for his support and help. He also said that he planned to return to the States in November to complete his doctoral studies. These plans ultimately fell through, however, because the Nationalist Government prevented him from leaving Taiwan. Later, we learned that in February of 1968, thanks to an introduction by Mr. Chao-chia Yang, he got married. One year, Professor Mendel was invited to lecture at Tunghai University, and Chi-ming Huang drove Professor Mendel to Taichung. As he was driving back along Taichung’s Qingshui Highway, Chi-ming Huang died in a very bizarre car accident.

The Chi-Ming Huang case is explained in detail in Ming-cheng Chen’s book, Forty Years in the Overseas Taiwanese Independence Movement, pages 96 to 98; and Professor Mendel’s book, Formosan Nationalism, pages 166 to 167.

8. A large advertisement calling for “Formosa for Formosans” is publics in The New York Times, November 20th, 1966.

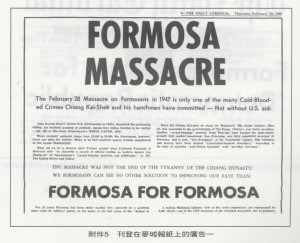

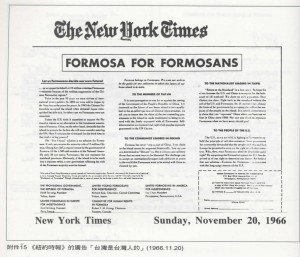

In 1964 in Philadelphia, Fu-Chen Lo and James Chin-Chun Su came up with the idea of using an advertisement in America’s best-selling and most influential newspaper to express the Taiwanese people’s desire to “pursue freedom, democracy, and independence.” Inspired by the publication of “A Declaration of Formosan Self-salvation” by Ming Min Peng, Tsung Ming Hsieh, and Ting-chao Wei in September of that year, the Canadian Human Rights Commission recommended that they publish a large advertisement in response. In 1966, after the establishment of UFAI, it was decided that on the Sunday before the UN discussed issues related to China, they would publish a half-page spread in the most famous newspaper, The New York Times. The Chairman of the Central Committee, Suy-Ming Chou, was put in charge of raising the funds to run the advertisement.

Sales for The New York Times were four times higher on Sundays than on weekdays, so advertising costs were extremely high; a half-page ad cost $4,000. Tai-cheng Kuo of Japan’s Republic of Taiwan Provisional Government, Koo Kwang-ming of Japan’s Taiwan Youth, and I-ming Huang of the Canadian Human Rights Commission pledged $500 each. The United Formosans in Europe for Independence also pledged $50, and the rest was raised by UFAI. Using his connections and good interpersonal relationships, Suy-Ming Chou asked for donations everywhere. Individuals from Madison, New York, and Philadelphia contributed the most to the fundraising campaign. However, the advertising costs were due 3 days prior to publication, and the total amount fundraised was still short by over $1,000. Thus, Suy-Ming Chou borrowed money from the University of Wisconsin Faculty Welfare Society and was prepared to pay off this debt himself. Fortunately, after the advertisement was published a great number of people were very moved, and donations came pouring in, thereby paying off all the expenses of the advertisement. With an additional balance of $350, he decided to publish a collaborative journal with submissions from Independence alliances in the United States, Canada, Europe, and Japan, titled Independent Formosa.

The advertisement was published on November 20th, 1966 with the headline, “Formosa for Formosans.” The advertisement introduced the idea of Taiwanese self-determination, and it detailed what the Taiwanese people wanted from the United Nations member states, the leaders of the Chinese Communist Party, the Taipei Kuomingtang government, and the American people. Nine days later, on November 29th, the UN still decided to recognize the Republic of China and refuse membership to the Chinese Communist Party. Generally speaking, however, the response to this advertisement was very good. The greatest gains were that they were able to symbolically represent the unity of the overseas Taiwanese community and lay the foundation for the World United Formosans for Independence (WUFI).

9. A Period of Growth and Maturity for UFAI (July 1966 to December 1969) and Preparations for the Establishment of the World United Formosans for Independence (WUFI)

The first UFAI national United Congress was held in Philadelphia on June 18th, 1966. The officers who were elected during this meeting are as listed below:

Executive Committee:

Chairman (also working on diplomacy): Edward Chen

Secretary: George Chang

Finances: Ren-chi Wang

Publishing: Hung-mao Tien, Ron Chen (also working on organization)

Research: Tzutsai Cheng

Island-related Work: Tron-rong Tsai

Organization: Frank Lai, Chiu-Sen Wang, Jackson Chiu, Liang-Shing Fan

Central Committee: Suy-Ming Chou (Chairman), Edward Chen, Ren-chi Wang, Tron-rong Tsai, Liang-Shing Fan, George Chang, and Fu-Chen Lo.

Additionally, other members like Powen Wang, Ho Rui Hsu, and Fu Yuan Hsu were very active in the organization’s activities as well.

Important achievements:

- The publication of Formosagram

- The translation of “A Formosan Declaration of Self-salvation” into English, and its widespread distribution

- The publication of a large advertisement in The New York Times

- “The Long March to Freedom” tour

The second United Congress was held on June 16th, 1967 in Independence, Missouri. The members are listed as follows:

Executive Committee:

Chairman: Ren-chi Wang

Vice-chairman: George Chang

Finances: C. C. Yang

Publishing: Frank Lai

Diplomacy: Liang-Shing Fan

Organization: Fu-Chen Lo

Fundraising: Ron Chen

Mobilization: Wen Chi Chang

Overseas Communication: Suy-Ming Chou

Central Committee: Suy-Ming Chou (Chairman), Liang-Shing Fan, George Chang, Fu-Chen Lo, Frank Lai, Ren-chi Wang, Tron-rong Tsai.

Important achievements:

- Published and publicly distributed the Independent Formosa journal in English, a collaboration between the American, Canadian, European, and Japanese organizations, while continuing to publish and distribute Formosagram for internal members

- Completed the UFAI Charter

- The Organization department continued to conduct the “Long March to Freedom” tour, visiting Washington D.C. Indiana, Illinois, Utah, Ohio, New York, Oregon, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and other states.

The third United Congress was held in Gary, Indiana. The members are listed as follows:

Executive Committee:

Chairman: Tron-rong Tsai

First Vice-chairman: George Chang

Second Vice-chairman (and working on diplomacy): Lung-Chi Chen

Secretary: Tzutsai Cheng

Finances: Jackson Chiu

Organization: Frank Lai

Publicity: Fu-Chen Lo

Overseas Communication: Chiu-yeh Shih

Central Committee: Suy-Ming Chou (Chairman), Fu-Chen Lo, Frank Lai, Ren-chi Wang, Tron-rong Tsai, C. C. Yang, Tzutsai Cheng, Shao Liang Cheng, Wen Chi Chang, Chiu-Sen Wang (the last two members resigned).

Important achievements:

- Amended the charter to abolish the position of Chairman of the Central Committee and make the Chairman the organization’s representative. A second Vice-chairman position was added, and a decision-making committee was established to help coordinate the decisions regarding important policies. The six members of this committee were appointed by the Central Committee and the Chairman (Edward Chen, Michael S. K. Chen, Tien-ming Lu, Ho Rui Hsu, and the two Vice-chairmen).

- Strengthened UFAI’s communications with the allied organizations in Japan, Europe, and Canada, in order to encourage integration.

- January 1st, 1970: Taiwanese Independence Organizations in the United States, Japan, Europe, and Canada Integrate to Form the World United Formosans for Independence (WUFI)

When Koo Kwang-ming visited the U.S. in 1965, he talked to Professor Mendel, as well as Suy-Ming Chou, Hung-mao Tien, Teng-chun Li, and Jin-Sheng Jian of the University of Wisconsin, about the possibility of integrating with UFAI to form an international Taiwanese independence alliance. Koo Kwang-ming had a thorough understanding of the situation on both the international level and the island level, as well as a clear theoretical basis, eloquent oratorial skills, and a talent for leadership. When Suy-Ming Chou was working on overseas communication, the two kept in close contact. Suy-Ming Chou also occasionally exchanged letters with Rung-pang Ho, Ying-ming Chou, Ng Chiau-tong, Chin-I Wu, Koh Se-kai, and Munakata Takayuki. Suy-Ming Chou also frequently wrote to Professor I-ming Huang of the Canadian Human Rights Commission, as well as to Tsung-ting Chang, Yu-chiao Hsiao, and Wei-chia Chang (pseudonym Chien-chih Lai or I-chih Wang) from Europe. In 1969 when Teng-chun Li went to Japan to collect materials for his doctoral dissertation, he was able to have more face-to-face interactions and communications with the Japanese allies in the Taiwanese Independence Movement. Thus, it can be said that the establishment of a global Taiwanese independence alliance went smoothly, just like how “when water arrives, a channel is naturally formed.”

On September 1969, a preparatory meeting for the creation of the global Taiwanese independence alliance was held in New York. Tsung-ting Chang of the United Formosans in Europe for Independence, Che-fu Lin of the Canadian Human Rights Commission, and all the officers of United Formosans in America for Independence attended the meeting. After two days of discussion, they agreed to establish the World United Formosans for Independence (WUFI). Each organization would keep its independences, and they would elect the members of the Central Committee themselves, and then allow the Central Committee members to elect a leader. As a result, Tron-rong Tsai was elected to the position of Chairman, George Chang to the position of Vice-chairman, and Tzutsai Cheng to the position of Executive Secretary. Another 20 individuals were also elected to serve as committee members, and they decided to officially establish the organization on January 1st, 1970. The English-language publication, Independent Formosa, and the Chinese-language publication, Taiwan Youth, became the organization’s two official magazines. This massive integration of overseas Taiwanese communities was a new milestone in the Taiwanese Independence Movement. Moreover, in the ten turbulent years of their participation in the Taiwanese Independence Movement, the Taiwanese students at the University of Wisconsin, in the name of pursuing their ideals, fearlessly confronted the Kuomintang’s totalitarian dictatorship and played a pivotal role in a number of deeply inspirational events.

Excerpt from Self-awareness and Identity – Compendium of Overseas Taiwanese Movements from 1950~1990 /2015/06

Translated from 81.早期(1960〜1970年)威斯康新大學 台灣學生在台灣建國運動所扮演的角色/周烒明起稿•吳美芬整理/2014/12