Bringing Bananas to America

Authors: Fu-chen Lo and Rou-jin Chen

It was generally understand that Taiwanese overseas students in the US during the 1960s scraped by on the most meager of means. Taiwan’s per capita income at that time was $160. We were allowed to take out only $200. The Korean students said that this was still more than what they were allowed to take out — $160. No doubt, the war had inflicted poverty on all of Asia. I was fortunate to come from a more affluent background. Mother gave me $2,000 that she had illegally obtained from the black market for me to smuggle out. This was the same amount managed by another ex-classmate from my NTU days, Hsieh Nan-chiang. His father, Hsieh Kuo-cheng, was at the time Assistant Manager at the Taiwan Cooperative Bank (He also was the secretary-general of Taiwan’s Baseball Association. He would later come to be known as the Father of Taiwan’s Little League Baseball).

Taking $2,000 out of Taiwan was considered a big deal. At its peak exchange rate of 1 USD = 46NTD, $2,000 was equivalent to 90,000 NTD. You could buy half a piece of property in Taiwan with that money. However, at Customs, you didn’t need go to great lengths to conceal this money. It sufficed to put it in the pocket of your pants. Out of respect, customs officers did not subject students going overseas to a body search.

However, once you landed in the US, the money diminished in value, like a giant becoming a dwarf. The first time I ate a steak in an American restaurant, I spent nine to ten dollars in one shot. It was more money than what an entire semester at National Taiwan University had cost me (the tuition was 240 NTD for one semester). One semester’s fees at UPenn, on the other hand, cost $500. One spent on average $1 every day on food alone. The $2,000 would last at most a year. That’s why, even though Hsieh Nan-chiang and I were from affluent backgrounds, we still had to work part-time like the rest.

When I first arrived in the US, before I even started school, a student senior to me with good intentions handed a restaurant menu to me. Seeing the confused look on my face, he explained, “You have to memorize this if you want to work as a waiter.” It was commonly understood that overseas students all waited tables, so that they could pay their tuition. Being a waiter qualified you for tips. It was better than being a busboy which paid little.

In the end, I didn’t become a waiter. One day, I saw an ad in the school paper seeking house painters. With two other international students (one Japanese, the other Korean), I applied for the job. I was the only one who dared to reach for the highest spot. Growing up, I had never done anything so menial. I couldn’t help boasting about it when I got home that day.

Afterwards, I found another job at a hospital. This one required me to work from six to eight in the morning. All I had to do was deliver newspapers to the bedsides of two thousand patients. One month’s work brought in $160, almost the same as an average full- time worker. On a monthly basis, Chin-fun and I spent $60 on food and $40 on rent. The remainder was allocated for books. A book at that time cost about eight to twelve dollars.

The average overseas student had it much harder. If he was from a poor background, he really had to be careful how he spent his money. My friend, Su Chin-chun (蘇金春), who came to the US after graduating from the electrical engineering department at NTU, got into this mindset from the moment he left Taiwanese soil. Most take a plane to get here but he made the slow journey by sea to the US’s West Coast. It wasn’t even a normal passenger ship that he took to cross the Pacific Ocean but a cargo ship, as if he was a piece of cargo.

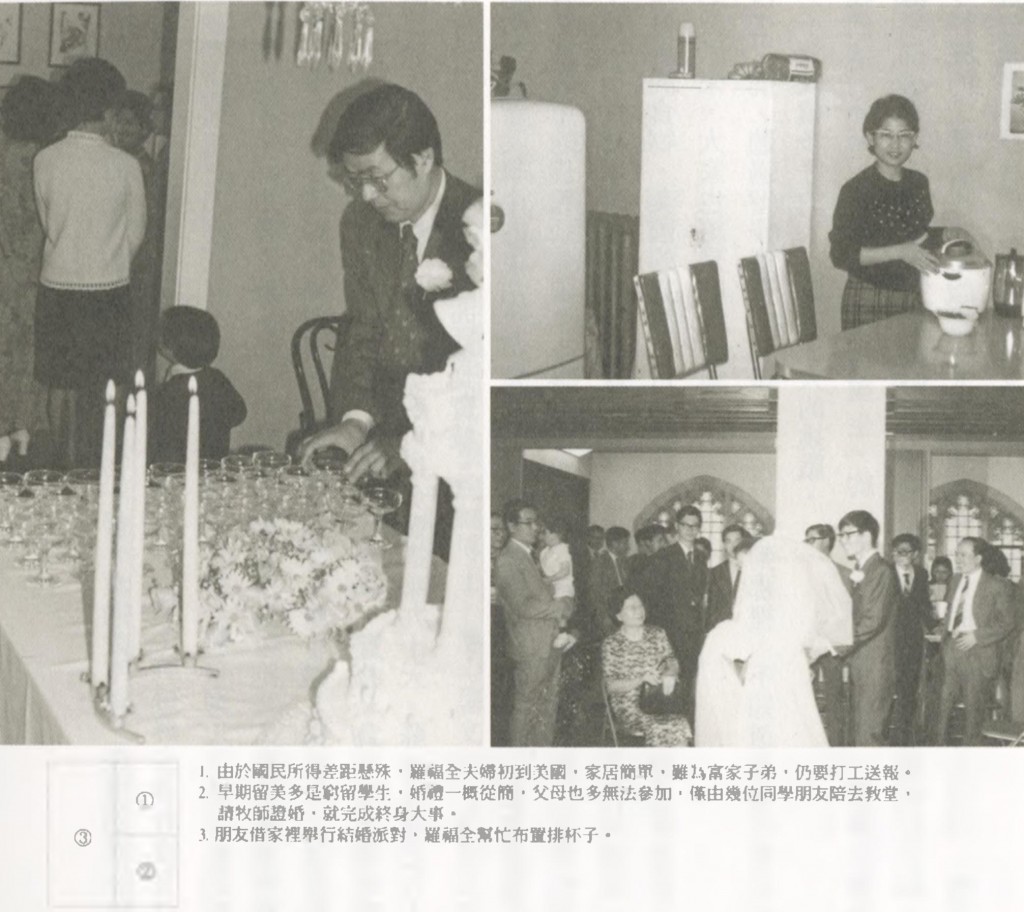

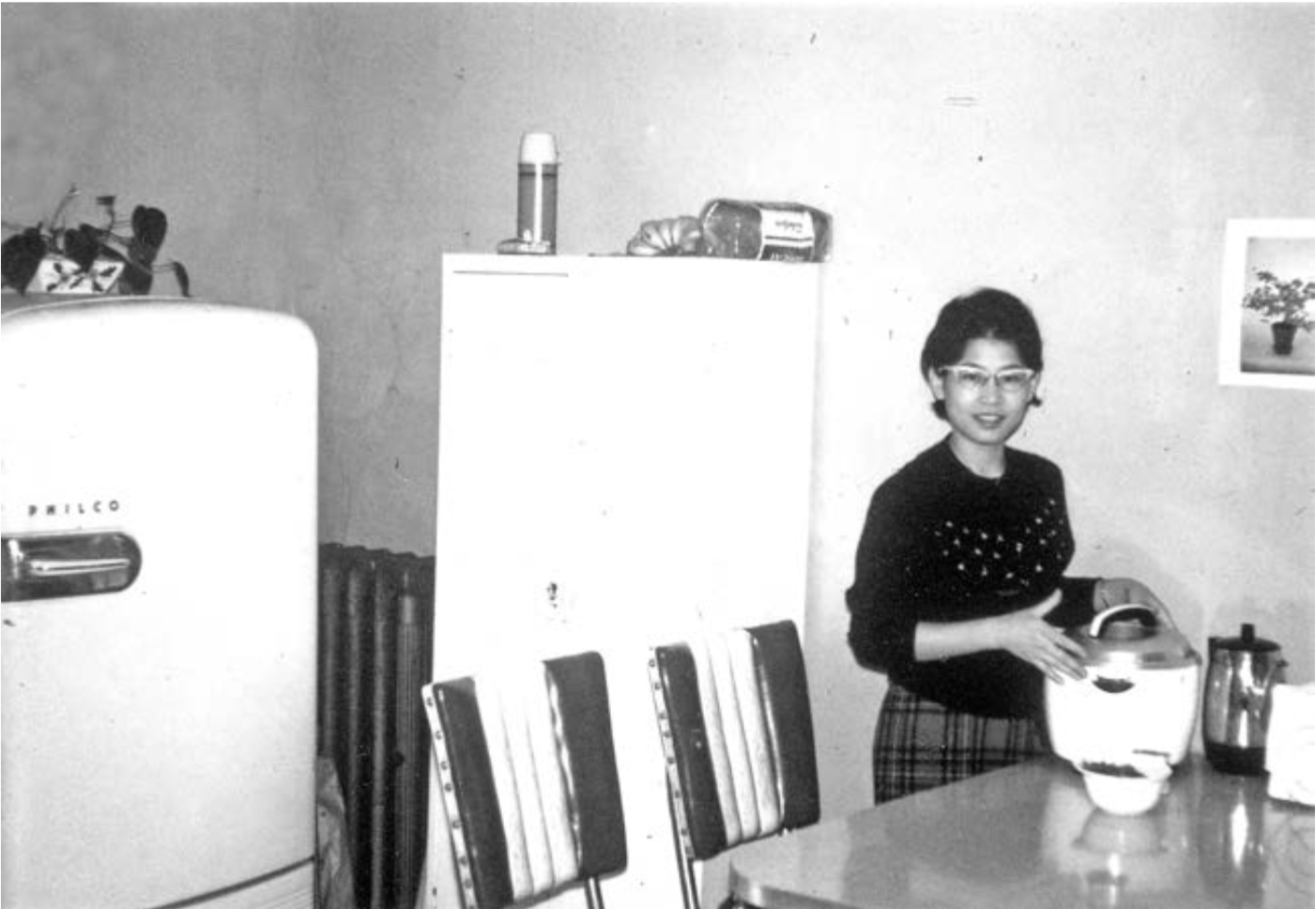

Owing to the great per capita income disparity between Taiwan and the United States, although Lo is from an affluent family, he and wife still led simple life in the US, and Lo even delivered newspaper part time.

The early Taiwanese overseas students tended to be poor, hence their weddings were often very simple and without their parents’ participation. Usually the bride and the groom would go to the church accompanied by friends, and let the priest marry them.

The early Taiwanese overseas students tended to be poor, hence their weddings were often very simple and without their parents’ participation. Usually the bride and the groom would go to the church accompanied by friends, and let the priest marry them.

Lo let friends use his home to hold the wedding reception. He helped setting up wineglasses.

Some overseas students used the time on the cargo ship to work part-time and earn a bit of pocket money. I don’t know if Chin-chun worked or not, but I do know that he took a stash of mullet roe, a Taiwanese and Japanese delicacy, and a basket of bananas on board with him. At sea, if the weather was good, he would take the mullet roe out to sun on the deck. If the ship rocked, causing the mullet roe to slip back and forth, he was busy making sure that the roe didn’t slip off the deck. Stopping over in Japan, he sold the bananas and mullet roes at inflated prices. With the money, he bought a windbreaker jacket and a camera before continuing on his journey.

When the ship docked on the US’s West Coast, Chin-chun got off the boat and boarded a Greyhound bus headed east. At that time, a $90 ticket covered travel for 90 days. With this ticket, Chin- chun crossed the country before finally arriving at the University of Pennsylvania.

In the 1960s, Taiwanese overseas students in the States all lived a frugal existence. Wang Po-wen (王博文), who was two years older than me, saved money on a book bag by taking the doctor bag that his father used on outpatient visits. By the time I arrived in the US, he had already earned his Master’s degree and started working. There were pear trees in the backyard of the farmhouse that he rented in the countryside. Usually farmers would allow the pears to fall naturally to the ground, where they could be eaten by horses. To think that a fruit we considered precious was fed to horses! Po-wen saved these pears. At gatherings, he often brought baskets of pears along, which we would eat with hearty enjoyment.

Before going to study abroad, you’d hear about the struggles of overseas students. But only the actual experience gave you a true understanding of the pressures of surviving abroad. Whether you were good at your studies or not, studying abroad represented a challenge in itself.

For our era of overseas students, the 1,000 out of 10,000 university graduates who qualified to go abroad, were considered society’s crème de la crème. Even though we didn’t have much in our pockets, our aspirations were grand. Almost everyone enrolled in prestigious schools. Our fathers and brothers back home borrowed money from relatives so that we could study abroad in the US. Even the most ungrateful one would apply himself with great determination to his studies as if his life depended on it.

Excerpt from From Taiwan and Back: A Memoir of Ambassador Fu-chen Lo, by Fu-chen Lo and Rou-jin Chen (2013), translated by Yew Leong Lee (2015).