TAIWANGATE

by Winston T. Dang

PREFACE

In the hearings on Taiwan Agents in America and the Death of Professor Wen-chen Chen before the Subcommittees on Asian and Pacific Affairs of the House Committee on Foreign Affairs, 97th Congress, First Session (July 30 and October 6, 1981), Representative Jim Leach from Iowa made the following statement:

“Finally, with regard to Dr• Chen’s tragic death, the United States government should demand that Taiwan reopen its investigation and make clear that warm relations between our governments can best be fostered in an atmosphere of frankness. Criminals, whether or not in government, must be held accountable• This was the lesson in America of Watergate and Koreagate. We expect of 1 Taipeigate1 no less.11

On July 3, 1991, it will be the ten-year anniversary of Professor Chen’s tragic death, and the case is still unsolved.

Mr. Leach1s expectation that the government of Taiwan would reopen the case for reinvestigation seems to be just another dream.

On May 9, 1991, Taiwan’s Investigation Bureau arrested a Taiwanese UCLA Ph.D. student, Jen-ran Chen (currently on leave), on charges of violating the Statute for the Punishment of Sedition in Taiwan. According to several newspapers in Taiwan, Chen was charged with sedition because of his activities while studying in the United States. The government1s Investigation Bureau claimed that he had been under surveillance since his arrival at UCLA in 1988.

These two cases are typical of the so-called campus spy network and the blacklist system used by the Chinese Nationalist (Kuomintang, KMT ) government in its attempt to control the Taiwanese people. While surveillance systems over students have always been common in Taiwan, the KMT-dominated government has also been using the same spy techniques on campuses from coast to coast here in the U.S. The spies are by no means professional: most are students without any background in surveillance. Some are in need of money, and the government provides scholarships for those willing to send reports back to Taiwan. Some act as informants purely out of patriotism for the government.

Regardless of the reason, these spies are all rewarded with high government positions when they return to Taiwan.

I can recall one day in 1978, when I attended a seminar at Harvard1s Department of East Asian Studies. As the scheduled speaker was from Taiwan, many other Taiwanese students were also present. Dr. Jerome Cohen, a Harvard professor, was seated next to me. While we watched the students fill the room, Professor Cohen leaned towards me and whispered, “There1s another KMT spy!” I could not understand why Professor Cohen would reveal his own student as a spy, though, he might have been joking• However, I recognized the Chinese student as someone very active in the publication of the “Boston Newsletter,” distributed by the Boston area Chinese Student Association and supported by the authorities in Taiwan. This man had also attended a pro-Taiwanese rally, feigning support for our cause. While at the rally, he and a group of his friends stood apart from the rest of us and remained silent. Some activists recognized his face and chased him away. A few years later, as a man in his early thirties, he went back to Taiwan and accepted a very powerful position in the government.

Such spy activity is clearly unethical. It appears that information gathered from this network might have led to the creation of the blacklist system, in which many overseas Taiwanese are either denied or permitted only restricted travel to and from Taiwan• For many, their participation in campus activities in the U.S. serves as their only “crime.” For some, it is merely their association with persons whom the government in Taiwan considers unfavorable which adds their names to the blacklist.

According to Taiwan’s Bureau of Entry and Exit Statistics (in 1990), some 5,129 applications for entry into Taiwan and 1,217 applications for exit were denied pursuant to the National Security Law. Of these, 2,689 applications for entry and 890 applications for exit were denied on the basis of suspicion of posing “grave security risks to national security or social stability.” (Quoted from the State Department’s “Country Reports On Human Rights Practices For 1990, published in February, 1991 p.874” ) According to the most recent estimates, some 800 to 1,000 Taiwanese living in the United States, Canada, Japan, South America, and Europe are still refused entry into Taiwan or have been harassed even if they have managed to obtain a temporary entry permit. Some non-Taiwanese scholars such as Dr. Marc Cohen of Washington, D.C., Former U^S. Attorney General, Ramsey Clark of New York, and Dr. Gerrit van der Wees of Holland also have been placed on the blacklist.

On March 26, 1991, Representative Stephen J. Solarz was interviewed by two TV reporters from Taiwan. His remarks on the issue of “blacklisting” Taiwanese-Americans can be considered a moderate description:

“The problem that I have with the Taiwanese blacklist is the extent to which it apparently includes a substantial number of people who are law-abiding citizens or residents of the United States and who would undoubtedly obey the laws of Taiwan if they are permitted to return there. So, this blacklist is not designed to protect the security of Taiwan. It is designed to prevent people who may not agree with the views of the ruling party from returning to Taiwan. As someone who believes very much in democracy, I think it is a practice which has to be considered as unacceptable.”

It is not only unacceptable but also inhumane to many overseas Taiwanese who have been involuntarily exiled for many years. They have been barred by the Taiwan authorities from seeing their beloved families, or even from visiting their ailing or aged parents before they passed away.

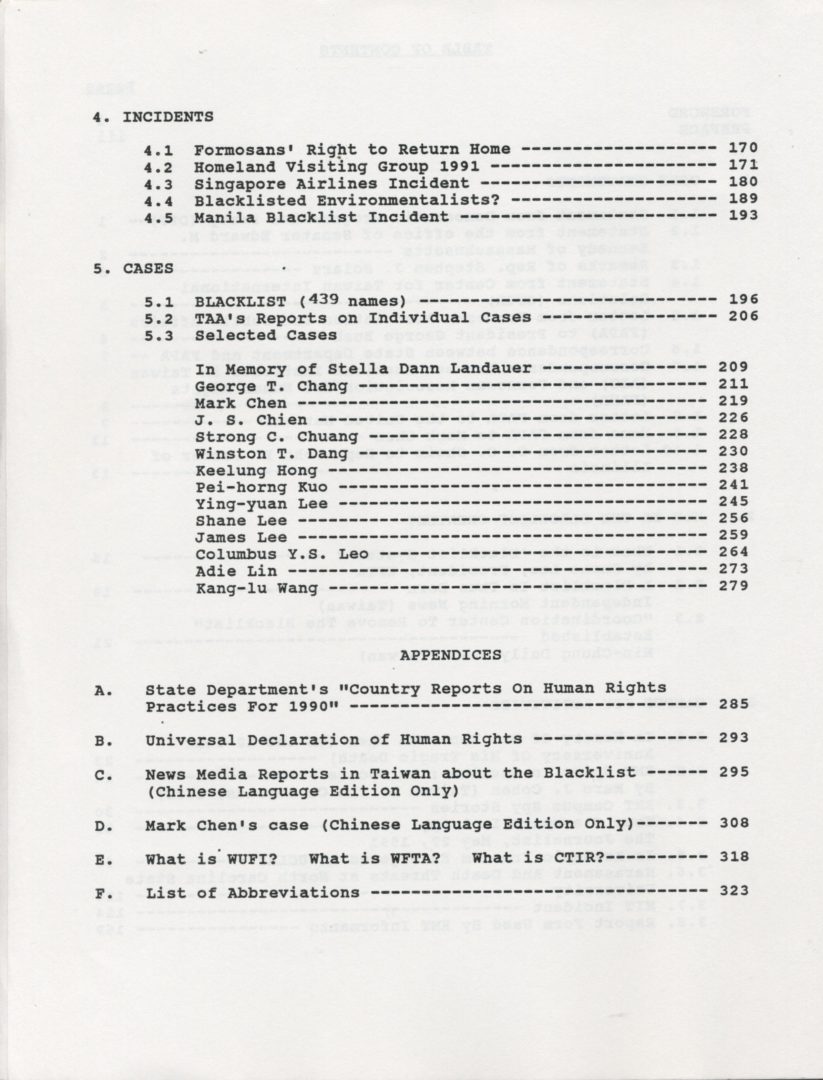

The following is a compilation of articles, including incidents of this so-called campus spy activity, such as the spying charges at MIT (1976) and the most current one, the case of the UCLA student arrested in Taiwan (1991)• We also included an article, “Your Classmate is a Spy,” printed in The Journalist during the week of May 27, 1991, which disclosed some detailed information about how the campuses have been monitored by the KMT-dominated government Investigation Bureau agents. Another goal of this compilation is to inform readers of how the blacklist was created and why people like Professor Wen-chen Chen and hundreds of other overseas Taiwanese have been blacklisted. Several cases have been used as examples in this book in order to show the struggles and real stories behind those overseas Taiwanese, both Taiwanese nationals (such as Kang-lu Wang, Pei- horng Kuo, and Ying-yuan Lee) and Taiwanese-born foreign citizens, who have had to deal with the blacklist as a result of their nonviolent use of freedom of speech.

As Senator Edward M. Kennedy said: “I join with other friends of freedom around the world in urging the Government of Taiwan to end the blacklisting of persons associated with Taiwan1s democratic movement. Recognizing this fundamental human right would be a significant step in enhancing the cause of freedom and liberty in Taiwan.11

(Winston T. Dang, Ph.D., July, 1991)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

工 would like to express my deep gratitude to the following persons for their help: Coen Blaauw, Strong Chuang, Steven R. Hsu, Tzuoh-chu Hsu, Mei H. Huang, Pei-horng Kuo, James Lee, Shane Lee, Adie Lin, Christine Sirko, D. M. Wang, Kung-lu Wang, and especially to David Tsai for his very valuable commentsf and to Tim Wang and Min-lu Chai for their efforts to reorganize the namelists. (Some names have been withheld by request.) I would also like to thank Taiwanese Blacklist Task Team (including the following organizations: WFTA, FAHR, TAA, FAPA, NATPA, NATWA, CTIR, and TC), Coordination Center to Remove The Blacklist (including the following organizations in Taiwan: INC, TAHR,

TAUP, FPCF, APT, FPPA, FTIR, TM, and NJ Cheng MF ) and WUFI for their supports.

Published in 07/1991

Donated by 劉格正 01/2017

Posted in 01/2017