UFI (United Formosans for Independence)

Author: Tsu-Yi Jay Loo

- The Origin of UFI

In December 1957, Tsu-Yi received his bachelor’s degree in Political Science. That same year, he applied for and was admitted to the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs Fellowship at Princeton University. The new school year didn’t start until September of the following year, so he moved to New York City to look for a temporary job. At the end of the year, Tsu-Yi rushed back to Philadelphia to meet with the other members of 3F. At that time, the members of the organization were slowly increasing, and 3F now included George Lu, Kenny Yang (Chao-chia Yang’s son), and Larry Kuo (from Tainan City). The main topic of the meeting was whether or not 3F could continue its operations. Some people recommended that we stop the Taiwan independence movement, while others suggested that we change 3F into a scholarly research society. Given the FBI’s investigation and the false alarm that 3F members might be arrested, these various reactions were understandable. However, by directly negotiating with the FBI’s lawyer, Tsu-Yi had already convinced the U.S. government of the fact that 3F was an organization dedicated to establishing a democratic nation, and that it had not violated U.S. law. As a result, he had won freedom of action for the Taiwan independence movement, so he proposed that they continue to promote Taiwan independence. The newly-joined members of the organization agreed with his opinion. Nonetheless, the majority of members felt that since 3F had been previously entangled with the U.S. Department of Justice, the organization needed to change its name. After discussion, they adopted the name “United Formosans for Independence” (UFI).

During the era of 3F, there were only a few rules of operation. This time, after a whole day of review and discussion, they formulated the main contents of the UFI charter. The next day, Tsu-Yi drafted and typed up the articles of the charter, and it went into effect on January 15, 1958. The mission of UFI is to establish a free, democratic, and independent Republic of Taiwan based on the principle of self-determination. UFI rejects all authoritarian dictatorships and colonial rule. During this meeting, Tsu-Yi Jay Loo was elected via secret ballot as the first president of UFI.

- Expanding the Scope of the Movement

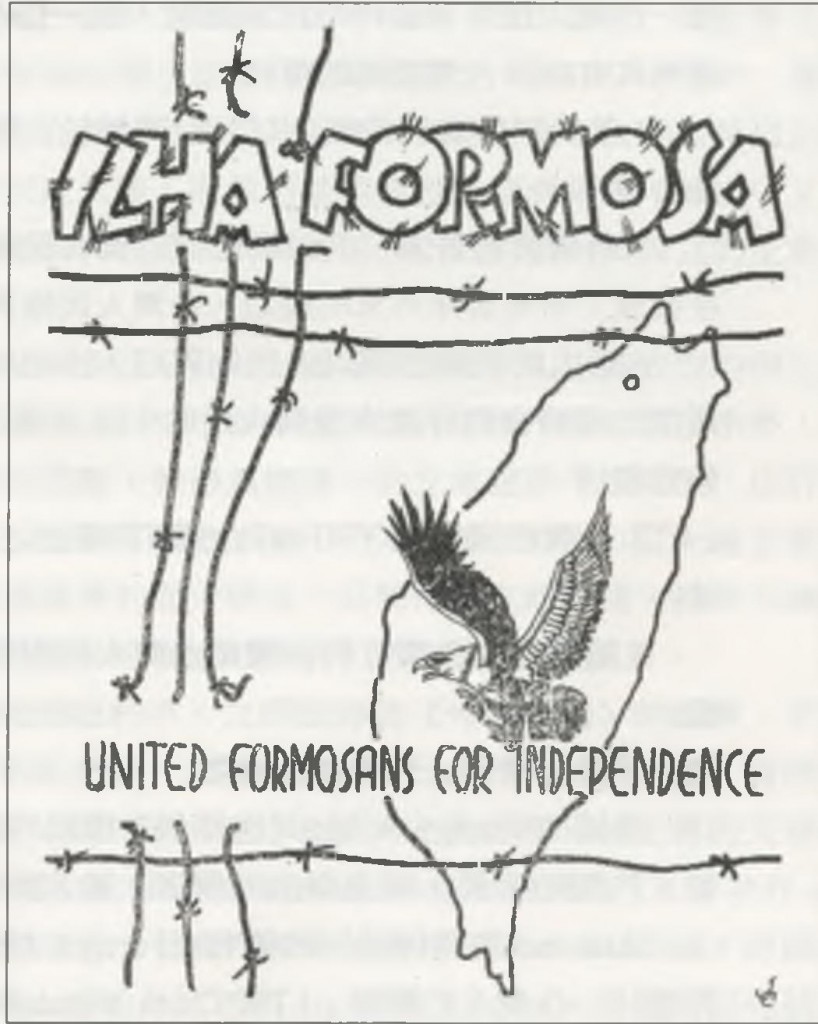

UFI continued to publish informational materials, which were aimed at instilling the ideas of democracy and Taiwan independence into Taiwanese students in America. The newsletter was renamed Ilha Formosa (Beautiful Island). From April 1958 until June 1961, 13 issues were published and distributed. In the opening letter of the first issue, Tsu-Yi called out to fellow Taiwanese, asking them to support the cause by publicizing the plight of Taiwanese living on the island, thus helping to win international support for Taiwan independence. At the same time, UFI announced that it would declare the Taiwanese people’s ardent desire for freedom and the right to self-determination to the UN, the U.S. Congress and political leaders, the mass media and the academic world.

Aside from Ilha Formosa, UFI also occasionally published topical papers or pamphlets called “Appeal for Justice,” which were distributed to congressmen, scholars, and the mass media. Tsu-Yi also went twice with Edward to visit members of the House of Representatives on Capitol Hill. Tsu-Yi discovered in the Congressional Record that there was a Congressman who had made a speech to Congress, expressing sympathy for the Taiwanese situation. Thus, Tsu-Yi and Edward got in contact with the Congressman, and the two of them went to visit him, expressing their gratitude and asking him to support the Taiwanese’s right to self-determination. They also met a second Congressman through Reverend James Dickson, who organized their introduction during a visit to the States. In 1960, John F. Kennedy was elected as President of the United States. He appointed former Connecticut Governor, Chester Bowles, as Under Secretary of State. Not long after his appointment, Tsu-Yi was able to schedule a meeting with Bowles, and he and Edward went to the State Department to visit him. Unfortunately, Bowles’ secretary said that Bobby Kennedy (the President’s younger brother and U.S. Attorney General) had asked him to attend an emergency, so he unfortunately was unable to meet any guests. Bowles ordered his two assistants to take Tsu-Yi and Edward to a nearby restaurant and discuss issues regarding Taiwan at lunch.

Shortly after UFI was formed, Tsu-Yi began corresponding with a number of prominent American political leaders and scholars. These luminaries included 1952 and 1956 Democratic presidential candidate, Adlai Stevenson; Professor of Political Science at the University of Chicago, Quincy Wright; Senator Wayne Morse; and George Kerr of California’s Hoover Institution.

In the spring of 1960, Mr. Ong Iok-tek launched a Taiwan independence movement in Tokyo with a group of Taiwanese students. On April 1st of that year, the first issue of the Japanese journal, Taiwan Youth, was published. On June 23rd, Tsu-Yi wrote to the editorial board of Taiwan Youth under the pen name Li Thian-hok, introducing UFI’s activities in the U.S. He also submitted a Japanese translation of Ilha Formosa’s May editorial, “South Korea’s Crisis and Taiwan,” to Taiwan Youth. On August 20th, the first issue of Taiwan Youth contained Tsu-Yi’s letter and the Japanese translation of the editorial. After that, the two parties continued to communicate by letter, as both were willing to cooperate with each another.

- Shared Convictions of the Taiwan Independence Movement

In the spring of 1961, UFI’s comrades in Tokyo proposed that they create a document stating their common beliefs. Tsu-Yi drafted the joint statement, and it was co-signed by Ong Iok-tek and Li Thian-hok. The statement was written in English, and its contents reflected the basic convictions of that era’s Taiwan independence movement. The statement is as follows:

We hold the following convictions to be fundamental to the cause of Formosan independence.

- What constitutes a nation is not a similar language or belonging to the same ethnic group, but having accomplished great things in the past and the wish to accomplish them in the future.

- The history of Formosa has been nothing but an incessant struggle of a freedom-loving people for liberty against unwanted intruders (i.e., The Dutch, Chinese, and Japanese).

- We Formosans share a distinct sense of national identity derived from sharing a cultural outlook, a set of values, and a common love of our native land. Our manifest sense of identity and our past struggles clearly endow to us a right to self-determination of our future.

- The only just and legitimate basis of an independent Formosa is the recognition that Formosa belongs rightfully to Formosans.

- Formosans are widely educated, diligent, and willing to defend their country. Thanks to American aid, the Formosan economy is developing. Relieved of outside pressure and given a chance to manage our own destiny, we Formosans are fully capable of building a viable and dynamic democratic nation.

- Our form of government must be based on the consent of the public, a respect for the rule of law and certain inalienable civil liberties. The government must establish long-term economic development plans in order to improve the quality of life for its people. The government must also improve the country’s cultural, social, and educational environments.

- Taiwan’s independence must not be reduced to a mere bargaining chip in the Cold War; an independent Taiwan must be a Taiwan that is both sovereign and permanent.

- To strive for a free and independent Formosa is the most effective way by which we Formosans can contribute to the cause of justice, humanity and peace for the world.

(Source: Li Thian-hok via the Taipei Times, with supplementary translations from T.A. Archives)

- Paper on Taiwan Independence Published in Foreign Affairs

The American journal, Foreign Affairs, is the world’s most authoritative forum for world politics. Contributors to the journal often include heads of state, high-ranking ministers, and prominent scholars, so the discourse is quite high level. On April 4, 1958, Tsu-Yi Jay Loo used the pen name Li Thian-hok to publish North America’s very first article on Taiwan independence in Foreign Affairs. The article was titled “The China Impasse – A Formosan View,” and it caused quite a stir in the American academic community. Nan-jung Cheng’s Freedom Era Weekly magazine published a book titled “The Rising Winds” in October 1999 and included in it was the Chinese version of “The China Impasse.”

In August 2001, Wen-huang Kang published a paper titled “The Democratic Progressive Party’s China Policy Evolution” in the 490th issue of the Japanese journal Taiwan Youth. According to Kang, the conceptual origins of the Democratic Progressive Party’s (DPP) principle of “One China, One Taiwan” came from two sources: (1) Li Thian-hok’s article, “The China Impasse,” published in the April 1958 issue of Foreign Affairs, and (2) Ming Min Peng’s “A Declaration of Formosan Self-Salvation,” published in September 1964. According to report, after President Chiang Kai-shek was informed of the discussion of Taiwan independence published in Foreign Affairs, he convened an emergency cabinet meeting to discuss how to deal with it. As a result, he ordered Dr. Tsiang Ting-Fu, the Chief Representative to the UN, to write a rebuttal to be sent to Foreign Affairs. But the editor refused to publish it. The Nationalist Government had no other option than to make thousands of copies of the article and send them to academic institutions and the representatives of each UN member state. Richard Cheng-san Lee, an oral history expert who lives in New Jersey, wrote an article titled “Li Thian-hok and Tsiang Ting-Fu” to describe the details of this event, introduce the main arguments of “The China Impasse,” and to express his opinion of Tsiang’s rebuttal. Lee’s article has been published in a compilation titled Freedom Calling (Edited by Li Thian-hok, published in December 2000 by Avanguard Publishing Co.).

Tsu-Yi was a mere student, so how was he able to write about Taiwan independence in Foreign Affairs with such conviction that it made Taiwan independence a serious topic in international discourse?

The University of Minnesota had tens of thousands of students, with ten thousand graduates each year. In accordance with the University of Minnesota’s graduation requirements, each student must submit a senior thesis. In the fall of 1957, Tsu-Yi Jay Loo finished his thesis, which focused on analyzing Taiwan’s political and economic issues. The thesis criticized the National Government’s economic policies, which focused on national defense (in preparation for counter attacks on the mainland), while ignoring basic infrastructure and economic development. The paper also recounted Taiwan’s history, including the causes and aftermath of the 228 incident. The rest of the paper espoused the legitimacy of Taiwan independence.

One day, Tsu-Yi’s faculty advisor, Charles McLaughlin, Professor of International Law, called Tsu-Yi to his office to congratulate him. His thesis had won the 1957 Graduation Thesis Championship Award, and though the prize money was a small amount, it was a signal honor. This was a great encouragement to Tsu-Yi. Since it was chosen from ten thousand theses, perhaps it was good enough to be considered by the publishers of Foreign Affairs. Not long after submitting the original draft, he received a reply that the article was too long to publish. But, if Tsu-Yi was willing to remove the economics section and simplify the historical portion, shortening the entire text to approximately 5,000 words, the article could be published. The thesis was reduced and revised twice before the editor was satisfied.

In December 1957, Tsu-Yi traveled from Minnesota to New York City, where he immediately went to visit the editor of Foreign Affairs. He brought along a copy of the Taiwan Church’s Romanized New Testament Bible to explain the origin of his pen name, Li Thian-hok. At the time, the editor told Tsu-Yi that his article would be published in the January 1958 issue. A few days later, he called to apologize, saying that the publication of Tsu-Yi’s article needed to be delayed until April because the Soviet Union’s Head of State, Nikita Khrushchev had suddenly submitted his paper “On Peaceful Coexistence,” which needed to be squeezed into the January issue. Contributors to the April issue included President Truman’s Secretary of State, Dean Acheson; UK’s former Chancellor of the Exchequer, Peter Thorneycroft; Italy’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, Amintore Fanfani, Indonesian Vice President Mohammad Hatta, and then-Harvard Professor Henry Kissinger; all prominent and high-ranking individuals.

- The Basic Theoretical Principles of the Taiwan Independence Movement

3F and UFI laid the theoretical foundations for the early Taiwan independence movement. The theory uses five different perspectives to talk about the legitimacy of Taiwan independence:

- International Law: In 1895, the Qing Dynasty ceded Taiwan and the Penghu Islands to Japan in perpetuity. In 1945, the National Government took control of Taiwan, but it never obtained Taiwanese sovereignty. In 1951, Japan gave up sovereignty of Taiwan and the Penghu Islands in the Treaty of San Francisco, but the treaty did not specify to whom sovereignty over Taiwan and the Penghu Islands would be granted. According to the UN Charter, the Taiwanese people have the right to determine Taiwan’s future.

- History: Starting from the Dutch occupation (1623-1662), the establishment of the Kingdom of Tungning and the rule of Koxinga’s family (1662-1683), the inclusion of Taiwan in the Qing realm (1683-1895), and the Japanese occupation (1895-1945), the history of Taiwan shows that it has never been an integral part of Chinese territory. For generations, the inhabitants of Taiwan fought for their freedom by resisting all foreign rulers. Thus, the current independence movement is a continuation of the Taiwanese people’s 400-year struggle. The March 1947 massacre, martial law and the period of White Terror have all proved that the Nationalist Government is an alien regime. Only by overthrowing the Nationalist Government can the Taiwanese people build a free, democratic and independent country.

- Politics: The Kuomintang and Communist Party are alike in copying Lenin’s single-party autocracy. The Kuomintang has monopolized both political and economic policies. In the army alone, there are 25,000 political surveillance officers to prevent mutiny. The secret police are also everywhere, arresting, torturing, imprisoning, and even shooting dissidents. The Chiang regime discriminates against Taiwanese people, forcing colonial rule upon them. The Chinese population is merely 1.5 million people, while the Taiwanese population is 8 million. Nonetheless, of 700 legislative seats, only 8 are held by the Taiwanese people. The goal of the Taiwan independence movement is not just the abolition of such unequal and undemocratic foreign authoritarian government. The movement calls for progress: the establishment of a new country that is democratic, independent and dissociated from Chinese ties, because Taiwan belongs to the Taiwanese people who make up its main body.

- Economics: Chiang Kai-shek has called for a counterattack against the mainland with 600,000 troops. By ignoring Taiwan’s economic development, he has negatively impacted Taiwan’s economy. Though Japan is only as large as the state of California and lacks many resources, the Japanese economy is far ahead of the rest of the Asian countries. Taiwan is quite similar to Japan; with hardworking and educated workers, the Taiwanese should be able to develop a self-reliant economy just like Japan.

- Nationality theory: Taiwanese people are not Chinese. National identity is formed from three factors. The first is having been born and raised in one’s country, and thus feeling love and affection towards one’s homeland. The second is common political and economic interests. The residents of Taiwan are a destined community; in order to protect their freedom, lives, and property, the Taiwanese have no other option but to build a new, democratic and completely sovereign country. The third is the shared historical memory of the Taiwanese people. The Taiwanese have a collective consciousness, and in that consciousness is the desire to write a new history. As French scholar Ernest Renan said, “The sense of nationality, as distinct from race, is not biological but spiritual.”

The ideas presented above are the beliefs of the Taiwan independence movement of 45 years ago. Things have changed since then. Now, Taiwan faces military threats, economic offensives and psychological warfare from China. Internally, the opposition party, as well as a number of media channels and Taiwanese businesses owe loyalty to China. This combination of external aggressions and internal subversion has created an extremely dangerous situation. The arguments for Taiwan independence are in urgent need of updating, so they can be adapted to today’s Taiwan.

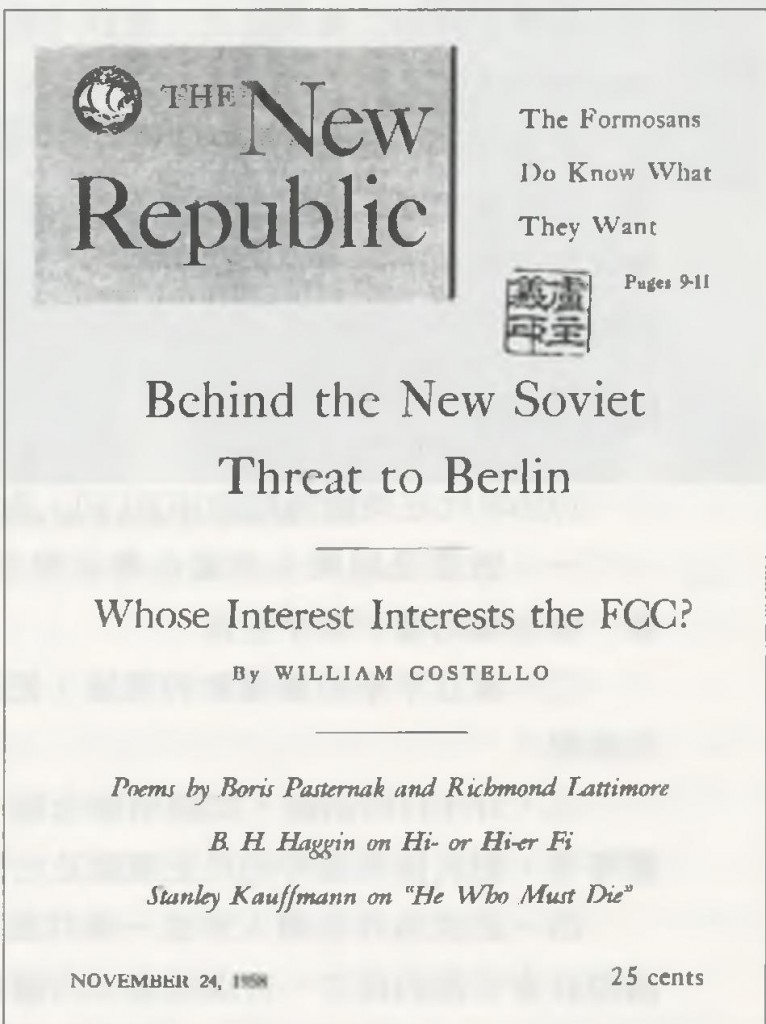

- Debate in The New Republic

In the fall of 1958, an American magazine, The New Republic, published a great debate regarding the future of Taiwan. Participants included:

Lord Michael Lindsay, a British Lord and a senior professor at Australian National University.

John Fairbank, an eminent Chinese Historian at Harvard University.

Denis Healey, a member of British Parliament and later, Foreign Secretary under the Labour Party government.

Denis Warner, a senior Australian journalist, Far East issues expert, and former Harvard Nieman Fellow.

Li Thian-hok, then graduate student at the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, Princeton University.

On October 6, Michael Lindsay published an article called “Formosa’s Future.” According to his observations, the National Government under the leadership of Governor Chen Cheng had eliminated corruption, rectified the military and implemented land reforms. Though Taiwanese people’s freedoms are still somewhat restricted, their situation is better than that of the Chinese people. The younger generation receives Chinese education, and though they don’t want to be unified with Communist China immediately, they recognize that Taiwan is part of China. Taiwan’s future appears uncertain, and the possibility of a military conflict is high.

Following this, Denis Healey responded with “Formosa and the Western Alliance,” published on October 13th. In his article, Healey said that U.S. policies supporting the Chiang regime were beginning to disintegrate, that Taiwanese are not Chinese people, and that Taiwan should be entrusted to the UN, so that the Taiwanese people can decide their own futures via a referendum. On the same day, John Fairbank also accepted The New Republic’s invitation to respond, writing a commentary titled “Formosa Through China’s Eyes.” In it, he stated that it would be difficult to have a referendum. If a democratic government could be achieved through an election process, this would be a more feasible method of national self-determination. Taiwan has become a bastion of traditional Chinese culture; the U.S. should support Taiwan’s independence from China.

On November 3, Denis Warner wrote a report from Taipei, titled “What are the Prospects for an Independent Formosa?” In his opinion, Taiwanese values are very different from Chinese values. Though the Taiwanese have the opportunity to establish their own country, they are submissive by nature and do not have a specific vision for Taiwan’s future, nor do they know what they want. In accordance with the unspoken understanding between the two sides, Taiwan will continue to maintain the current status quo of having a divided “One China.”

On November 24, Tsu-Yi published an article titled “The Formosans Do Know What They Want,” under the pen name Li Thian-hok. This article was latter translated into Chinese by his friend, J. H. Liao and published under the title “Comments on the Kuomintang Rule of the 1950s” in “Freedom Calling” (2000, Avanguard Publishing). The article summarized all of the earlier arguments and added its own commentary. There were two main components in the article: (1) Refuting the claim that the National Government had reformed itself by analyzing various instances of political oppression, economic problems, and how the government has used land reform to exploit farmers; (2) Asserting that under martial law, it was a given that the Taiwanese were unwilling to openly express their opinions about the future of Taiwan. If there comes a time when Taiwanese no longer have to worry about the dangers posed to their lives and personal freedoms, they will be able to express their true feelings and the vast majority of Taiwanese will definitely choose a democratic, free and independent country.

After the conclusion of the debate, Chu Fusung, a National Government Envoy (and later Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of China) who was residing in Washington D. C. at the time, also submitted an article that severely criticized Tsu-Yi Jay Loo’s discussion points. Fortunately, the editor of The New Republic sent Chu’s article to Tsu-Yi and invited him to respond. Thus, this small debate was published in the December 22nd issue of the magazine.

45 years later, time has come and gone, and Taiwan has achieved considerable success in economic development and democratization. Nonetheless, the future of Taiwan that concerned all these experts still remains uncertain. I earnestly hope that my fellow compatriots in Taiwan will call out, expressing their desire for Taiwan independence as soon as possible, so that I will not be disappointed and remembered in history as a liar. The 2004 Presidential election is a great opportunity for the Taiwanese people to express their choice.

Conclusion

3F and UFI, established in the U.S. in the 1950s, played the following roles in the overseas Taiwan independence movement:

- Enlightened and organized ambitious Taiwanese students across the United States, sowing, watering and sprouting the seeds of the Taiwan independence movement.

- Laid the theoretical foundations of the early Taiwan independence movement, introducing the concept of Taiwan independence onto the international forum, thereby making it a relevant political discussion topic.

- The activities of 3F and UFI, filing a petition to the UN, lobbying members of the U.S. Legislative and Executive branches, contacting academics and the mass media, helped lead the way for the overseas democracy movement and Taiwan independence movement which continued to grow.

- Fostered the consensus among overseas Taiwanese that Taiwan should establish a properly named, internationally recognized, free and independent country: that this would be the only way to safeguard the people’s lives, freedoms, and property.

- Since 3F and UFI’s members were also actively participating in their Taiwanese associations, 3F and UFI also contributed to the later formation of the Taiwanese Association of America (TAA).

Today, there are many relatively unknown allies of the Taiwan independence movement who dedicated time and energy of their youth to fight for Taiwan independence. Many were blacklisted and had no way to return home, so they had no other option than to be naturalized as Taiwanese Americans. Nonetheless, their love and affection for their homeland never changed. I hope that Taiwan will finally gain independence one day, bringing comfort and pride to these unknown heroes.

The UFI publication, Ilha Formosa

On November 24th, 1958, Tsu-Yi Jay Loo published “Formosans Do Know What They Want” in The New Republic

A group photo with Tsu-Yi Jay Loo and his wife (right side), and Fu-Chen Lo and his wife, Ching-Fen Mao (left side), taken in 2002.

Excerpt from Self-awareness and Identity – Compendium of Overseas Taiwanese Movements from 1950~1990 (June 2005)

Translated from 126. 台獨聯盟UFI (United Formosans for Independence)/盧主義/2015/04