PhDs Take On Naval Divers at Williamsport

Authors: Fu-chen Lo and Rou-jin Chen

In the 1960s and 1970s, Taiwan’s Little League baseball team won game after game on American soil at Williamsport, Pennsylvania, bringing much glory to the Taiwanese of that generation. Since I lived in the vicinity, I went for two of the first three competitions.

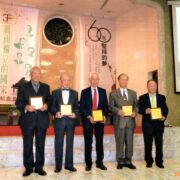

In 1969, we were represented by a team called Golden Dragon. By the time this was reported in the newspapers, I had already gotten wind of it through a newsletter sent by WUFI encouraging overseas students to attend and cheer their compatriots. I designed a bronze trophy that with the phrase, “Viva Our Little Brothers!” engraved in English and Chinese and “Pittsburgh Taiwanese Association” at the bottom.

WUFI also decided to hang a banner which read “Team of Taiwan” and the Chinese words “台灣隊加油” (“Go, Taiwan, Go!”) to let everyone know that one of the two teams playing on the field that day hailed from Taiwan. Despite our lofty-sounding title, “World United Formosans for Independence,” we only had a couple hundred members in the US. That day, over 200 Taiwanese from different Taiwanese associations came to Williamsport to watch the game, but only 20 WUFI members were on site. Yale Professor Chen Lung-chi gave a speech. Lai Wen-hsiung (賴文雄) and Cheng Tzu-tsai (鄭自才) held the banner while I stood at the center. Cheng Tzu-tsai would later be one of the main players in an assassination attempt on Chiang Ching-kuo in New York.

The game started smoothly without any hitch. That year, the Golden Dragon team was led by the Secretary-General of Taiwan’s Baseball Association, Hsieh Kuo-cheng (謝國城). His son Hsieh Nan-chiang (謝南強), who had been my classmate in the Economics Department at National Taiwan University, also came to watch the game. Seeing me, he joked that his role there was to oversee the laundry of the team’s smelly baseball uniforms. Naturally, I presented the trophy on behalf of WUFI.

The game ended with Golden Dragon as the winners. This was Taiwan’s first win at Little League World Series in Williamsport. We all were smiling proudly from ear to ear. The next moment, however, five or six Chinese men built like martial-art experts emerged from nowhere to snatch away the pole that Cheng Tzu-tsai was using to hold up the banner. A fight then ensued. The troublemakers realized that they were outnumbered by people from the Taiwanese camp and they quickly retreated.

At 1971 Little League World Series, Chair of WUFI, Chang Tsan-hung, was informed beforehand that the Kuomintang was mobilizing their supporters to the baseball stadium. He thought of an ingenious idea to rent a plane that would display a banner with the Chinese words “台灣獨立萬歲” (“Long Live Taiwanese Independence”) followed by “GO GO TAIWAN.” Some joked, “Taiwan has an Air Force!” But in truth, it only cost $260 to hire the pilot. On the ground, the Kuomintang party made and distributed tens of thousands of Chinese flags to the spectators at the baseball stadium. Still, the sea of flags they waved were no match for our plane circling above.

At the next series in 1972, still sour at what had happened a year ago, the Kuomintang Party sent massive reinforcements to Williamsport.

A friend’s son, who was still in elementary school, came up with a great idea. Using a potato, he carved out a seal of Taiwan. He stamped the shape of Taiwan on flyers that were distributed at the stadium. This boy, Chang Yi-jen (張怡仁), would later become a distinguished student at West Point. In fact, so distinguished that he was one of those honored with a face-to-face meeting with US President Ronald Reagan (It was customary for the US President to meet the top six students from West Point every year.)

In Taiwan, military school would only be an option if you didn’t get into university. That is not the case in the US. To American students, military school represented both a challenge and an honor. Entry into West Point was highly coveted. To get into West Point, you needed to have Harvard-level intelligence and an even better physical shape. A West Point student did not have to pay for his education, but in return he had to serve 5 years after graduation. Upon completion of military service, he was free again to choose his own path. Chang Yi-jen ended up going to graduate school at Columbia University.

Young Chang Yi-jen’s peaceful act of distributing flyers was no match for the violent atmosphere in the stadium that day. Before the game, we heard that the Kuomintang Party would be sending sixty Boston-trained naval divers to the stadium. Now, sixty may not sound like a big number, but we were grossly outnumbered.

Upon hearing the news, a few of the Taiwanese association members chickened out. In the end, only sixteen of us showed up fearlessly at the stadium, with bandanas on our heads to express our resolve.

Being outnumbered wasn’t our biggest problem. We were PhDs, not fighters. “Cracking eggs against a rock” was more like it. Chang Tsan-hung came up with an idea. We would all keep a hidden stash of salt in our pockets. If push came to shove, we could throw the salt in our aggressors’ eyes. Of course, none of the salt ended up being used.

Next to the Williamsport stadium was a little slope, where the sixteen of us stood. When the game ended, the sixty naval divers armed with iron bars wrapped in cloth surrounded us. A reporter from China Times shouted “They’re one of us too! Don’t beat them up!” Ironically, that was when the iron bars started swinging. Not knowing how to fight, I was beaten all over and I still have a scar to show from this incident. My glasses were smashed as well, so I couldn’t make out what happened afterwards.

But Chin-fun saw it all. She had brought our two sons along and was standing on the other side of the slope. With one hand, she held the hand of six-year-old Ted and she carried two-year-old David in the other arm. Seeing that we were getting beaten up from afar, she panicked and yelled at an overweight police officer, who was also watching the violence unfold and not thinking at all to intervene. “What’s the matter with you? Why aren’t you doing anything?” No soon after the words came out of her mouth when three Chinese men shot out of nowhere and pushed her roughly and spit out the question, “Does your husband belong to the World United Formosans for Independence?” Before Chin-fun had a chance to reply, a police helicopter arrived at scene, scattering the sixty men and saving the day.

With my hand injured, I could not drive the car. A friend drove us two hundred kilometers back to our home in Pittsburgh. That night, Chen Gu-ing (陳鼓應), a former Professor of Philosophy at National Taiwan University visited me, marveling at our courage for taking on the sixty naval divers. I said, “To each his own. Beating up someone simply for disagreeing with you, that’s just plain barbaric.” Those few years at Williamsport, I deeply believed that we were simply a group of intellectuals inspired by the democratic air we breathed in the US. We decided to do something about the unjust system oppressing our homelands. We couldn’t not do anything. We all wanted the best for our homeland, and to do so, we had to help bring about change. We had no knives or guns. We were only scholars who wanted to make a revolution happen. The Kuomintang party lumped us with the Communists, but this was in fact a perversion on their part. We were nowhere as large as the Communist Party for one, and certainly not the terrorists or evil people that they made us out to be.

Taiwan’s little league baseball team Golden Dragon came to Williamsport, Pennsylvania to compete for the world cup. Taiwanese overseas students went as a group to cheer them up. WUFI hang a banner which emphasized this team is from “Taiwan.”

Our headquarters in Pennsylvania rented a Post Office box (P.O. Box 7914). Because phone calls were expensive at that time, all communication was conducted via mail. The first time I went to collect letters at the post office, I was approached by an FBI agent. The first question he asked was, “Are you a communist?” During that time period, there was nothing more loathsome in American eyes than a Communist. Without a doubt, someone from the Kuomintang had (mis)informed the FBI about us.

If you take away the label of “World United Formosans for Independence,” what remains? — The conscience of a thinker and the passion of patriot. Every week we would hold our meetings. And every week we brought to the table the aspirations we held for Taiwan’s future and the question of our inalienable democratic rights. My son David had a hard time understanding this. He asked, “Every week you keep talking about Taiwan’s future. Aren’t you tired?” I quoted Martin Luther King’s famous line back at him. “I have a dream!” Now why would I ever be tired?

Excerpt from From Taiwan and Back: A Memoir of Ambassador Fu-chen Lo, by Fu-chen Lo and Rou-jin Chen (2013), translated by Yew Leong Lee (2015).