張超英這個人

作者:李淑櫻

他,出生在台北富豪之家

他,單槍匹馬為台灣作行銷

淡然,快意,看盡時代風流的精采人生

有一天在教會中餐時間,秀梅拿了本書問筆者看過沒?書名很特殊叫”宮前町九十番地”(日文譯為“國際廣報官張超英”),為2006年在台灣出版時搶手的暢銷書,引起筆者的極大的好奇,她又說,書中提到的許多人物中或許也有妳認識的也說不定喔,是嗎?生動的文筆與戲劇性傳奇經歷的穿插.讓筆者為之心動並下定決心看完他.這才發現………果然被秀梅說中了,幾十年前筆者就已在台中民族路基督長老教會認識他的姨媽甘翠釵長老及他的表兄弟姊妹們.

張超英, 在常與張家互動的友人康真純的印象中,是一位樂於助人,平易近人沒有一點世家子的驕縱.而在與他有多年交情的李昂的序中—卻被稱為-阿舍,黑狗兄.至於為何如此的稱他?他又是一位如何的世家子?讀者抽空一讀便知. 的確,在筆者認知的聽聞中是非常少見的.或許也是因為他從小就因著長輩的關係而認識經政界的龍頭而有許多不可思議的經歷,並享盡榮華富貴的生活與排場,在日後有著串連性的美好關係而孕育成遇事無畏與定意完成心中對守護台灣的堅持.在順暢的文字中讀來容易讓人以為發生那些事好像不是什麼困難.筆者以為有很多時候很多事情,若不是有像他當時的職位與膽識,而且機會也不盡是憑空飛來的?真的會是那麼簡單嗎?若不是心存台灣,有心為台灣作點事,以作台灣人為榮,就算是有個機會,在作與不作間也仍然是有所選擇的空間啊!就說他在東京任職那段時間將日本簽證從兩週縮減為兩天的事吧!當張先生到任後發現在簽證上,存著比不平等條約還嚴重的作法,就是日本人來台灣觀光,到東亞關係協會只需24小時即可拿到簽證,而台灣人要去日本的簽證卻需要兩個禮拜,日本政府以雙方無邦交為由行欺人之實,實際上簽證手續根本全程在台北辦理,政府官員與有辦法的人ㄧ樣可以迅速取得,沒有特權的老百姓則必須一大早五點就去排隊受盡折騰.張超英一心想為台灣人出一口氣,於無意中發現日本外務省下的諮詢機構裡有一個 “觀光審議委員會”,他索取了一份名單,其中一位橋本女士是電視台有名的女製作人,就請朋友介紹認識.並開始遊說;以1980年來看,台灣一年有五十萬人次去日本,平均ㄧ人在日本消費一百萬日幣,台灣觀光客的屁股後面等於是跟著一部又一部的卡車,載滿各式日本電器和土產,加上台灣又有那麼多的留學生在日本,若有兒女生病,難道也得等兩個禮拜才能見到兒女嗎?橋本女士邊聽邊點頭,口頭上答應要想辦法.後來這位女士自掏腰包請觀光審議委員會其他委員吃飯商量,說服其他委員,形成共議,最後決定邀請外務省次官出席委員會會議,尾員們集中炮火質詢,要求改變現況.不到兩個月的時間,簽證時間就縮短為兩天了.

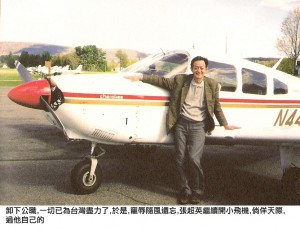

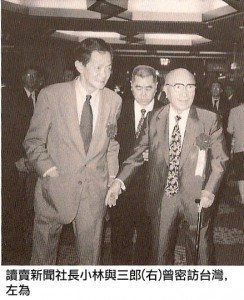

張超英,1933年出生於日本,東京.九個月後母親甘寶釵去世,由祖母扶養,是阿公阿媽的寶貝鑽石孫.1936~1945年間,父親張月澄(秀哲)在廣東,上海參加反日運動被禁返台,張超英於1939年入台北建成小學校,次年轉入上海日本第六小學,與父團聚,兩年後因戰亂返台,再入建成小學校,1944年轉入台北郊區北投小學校,1945年考入台北第二中學(現台北成功中學),1948年赴香港Royden House 英文書院就讀高中,1952年入日本東京明治大學政經學部1956年大學畢業,於1956~1957近日本上智大學研究所於1957年學成返台.並於隔年上任行政院新聞局第三處,從此他的人生舞台就與政治連結.1963年拍攝 “寶島三日”紀錄片獲國際馬賽觀光紀錄片銀座獎,1967年曾奉派美國紐約新聞處專員,1980年派駐日本東京新聞處處長,1985年公職退休離開東京.1994年再度出任新聞局駐日新聞處處長兼駐日代表處顧問,1998年第二次公職退休返台.2003年開始過人生的退休生活至2007年回歸天家享年74歲. 他的人生歷程經過了日治時代,威權時代,李登輝時代以及現在的本土時代.在各階段中,為了反對不自由,不民主,不公義而逬發出不同的火花,也為了執著於這個理念,對於他所經手的事;有人說他是 “漢奸”,也有人說他是 “台奸”有人歸他為 “宋派”,更有人指稱他是 “只會花大錢的公子哥兒”,對這些指稱他總是一笑置之.在三十一年的公務員生涯中,始終以超然的態度努力做他自認為 “對”的事, 他一心所想的就是要提高台灣人的尊嚴與地位.並追求符合自由,民主和公義的事.他所參與的國內外大大小小事件無法計其數,簡單舉一個例子來說;1975年,蔣介石去世,蔣經國繼掌大權的那一年,台灣的政治犯受迫情況相當嚴重.有一天他接到表妹盧千惠傳來消息說,謝聰敏已危在旦夕,要即刻救援,否則生命難保.謝聰敏因和彭明敏發表 “台灣人民自救宣言”及 “花旗銀行爆炸案”曾兩度入獄.他病危消息一出,台灣島內外都分頭尋找各種管道,熱切要援救他.張超英的太太嚴千鶴與張燦ㄏㄨㄥ的太太張丁蘭,及使命教會的林麗蟬去見國際政治犯特赦組織(International Amnesty)總幹事要求協助,短時間卻沒有下文.張超英於是打電話給紐約州聯邦參議員白克萊(James Buckley)的秘書 Ireen Payne 約時間,說千鶴有事要找她.第二天她與千鶴吃中飯時,千鶴詳細說明台灣政治犯的處境,請她轉告白議員,希望他能設法與台灣當局連絡,訊問謝聰敏的健康情形.不久白議員寫信給駐台美國大使館,要他們調查政治犯的情況.他的秘書很仔細週到,把信的副本寄給千鶴,並打電話告訴張超英,信已限時郵件寄發請他們放心.不到一週就接到謝聰敏獲准保外就醫的消息.謝聰敏出來以後,一直不知是誰奔走,只知台獨聯盟放出病危消息.直到2004年,千鶴把相關信件影印給他,謝聰敏才知幕後原因.而長年任職以來最令張超英先生引以為傲的,就是始終沒有加入國民黨.筆者認為這是一件極不簡單的事,以他所任的職位,長達三十一年能做到如此的切割,絕非一般的睿智.而他一口流利的英,日文更是讓人有求於他的利器.

套一句常被人引用的老生常談;到底是時勢造英雄還是英雄創時勢?當張超英在美國及日本上任期間,正值台灣在國際情勢非常不利的時刻,他卻能運用智慧突破重重外交困境,在美國與日本兩國的電視台及新聞界建立良好的人際關係,將台灣推上舞台.筆者認為若非本身具備足夠的有利條件,就是時機擺在眼前也是空有理想而無法施展作為.當讀者看了這本書之後或許有人會說因為他的出身有利條件,但除此之外不也都是他勤奮努力得來的嗎?說到他的勤奮努力,讓筆者想起書中的一段,當1948年,張超英14歲被送到香港英國人辦的Royden House就讀時,曾自己作主延請了三位家庭教師,一位教中文,二位教英文.但仍覺不足,就再登報徵求英文老師,他是這麼認真的學習英文,而這位老師卻不只教他英文,也教他民主思想,告訴他什麼是民主,什麼是言論自由和新聞自由,還講美國開國思想家傑弗遜的故事給他聽,經她洗腦,讓他非常憧憬當記者.根據張先生自己的說法, Mrs. Margaret Hampson 是他人生轉捩的重要因素,也啟發了他ㄧ生事業的方向.後來考取日本明治大學政經學部時,在夜間還去上智大學選修 “英文修辭學”加強英文能力.

套一句常被人引用的老生常談;到底是時勢造英雄還是英雄創時勢?當張超英在美國及日本上任期間,正值台灣在國際情勢非常不利的時刻,他卻能運用智慧突破重重外交困境,在美國與日本兩國的電視台及新聞界建立良好的人際關係,將台灣推上舞台.筆者認為若非本身具備足夠的有利條件,就是時機擺在眼前也是空有理想而無法施展作為.當讀者看了這本書之後或許有人會說因為他的出身有利條件,但除此之外不也都是他勤奮努力得來的嗎?說到他的勤奮努力,讓筆者想起書中的一段,當1948年,張超英14歲被送到香港英國人辦的Royden House就讀時,曾自己作主延請了三位家庭教師,一位教中文,二位教英文.但仍覺不足,就再登報徵求英文老師,他是這麼認真的學習英文,而這位老師卻不只教他英文,也教他民主思想,告訴他什麼是民主,什麼是言論自由和新聞自由,還講美國開國思想家傑弗遜的故事給他聽,經她洗腦,讓他非常憧憬當記者.根據張先生自己的說法, Mrs. Margaret Hampson 是他人生轉捩的重要因素,也啟發了他ㄧ生事業的方向.後來考取日本明治大學政經學部時,在夜間還去上智大學選修 “英文修辭學”加強英文能力.

提到上智大學,還發生一件讓張超英終生難忘的插曲;就是,有一次,週末受邀到當時日本最高裁判所的最高裁判長官的官邸參加一場為明仁太子選妃的舞會,而有機會與後來雀選為太子妃的美智子共舞.看到這裡,想必讀者諸君已興起了好奇,想一窺他精彩的生活事蹟了吧!

提到上智大學,還發生一件讓張超英終生難忘的插曲;就是,有一次,週末受邀到當時日本最高裁判所的最高裁判長官的官邸參加一場為明仁太子選妃的舞會,而有機會與後來雀選為太子妃的美智子共舞.看到這裡,想必讀者諸君已興起了好奇,想一窺他精彩的生活事蹟了吧!

附記- “宮前町九十番地”由張超英口述,陳柔縉執筆.時報文化出版企業股份有限公司於2006年8月20日出版.

The Person of Chang Chao-Ing

Nami Yang

Translated by: Philip Lee

- Born in a billionaire’s family in Taipei

- Single handedly lobbied for Taiwan

- Irreverent, playful, and lived a lifetime filled with fascinating events and charms of the times

My friend Shomei showed me a book on a Sunday at church during lunch and asked me if I have read it. The book was titled “Miyamae District Lot Number 90” (the Japanese edition of it was titled “International Lobbyist Chang Chao-Ing”). It was one of the bestselling books in Taiwan in 2006. She said in the book it mentioned many people who I may be acquainted with. Shomei’s comment piqued my interest and I began to turn the pages. I was quickly drawn into it by the author’s colorful story-telling writing style and his accounts of many well-known events and dramatic experiences. When I had finished reading it I realized Showmei was right: I did know some of the people mentioned in the book, namely the author’s aunt, Elder Gang Tsue-Tsai and some of his cousins. They were the individuals who I met decades ago at Min-Zhu Road Presbyterian Church in Taichung.

According to June, another friend of mine who was acquainted with the Chang family, the Chang Chao-Ing she knew was an easy-going and approachable person who was keen to help others, which was contrary to the stereotype of people born in prominent families. Yet, in the book’s preface he was characterized by Lee Ang who had known Chang Chao-Ing for a long time as a spendthrift and a playboy. I wanted to find out why he was characterized in such a manner and how his noble birth had shaped his character. As I began to read the book, I quickly realized that a person with his constitution was rare in my experience, i.e. having the access to the business and political leaders by the connections and influences established by his forefathers, having the resources to live a luxurious and carefree lifestyle, and having the proper upbringing for developing the courage of conviction to pursue the passion of his heart, the passion for defending Taiwan’s interests. By reading the smooth flowing passages in the book one may get a false notion that success came easily for him. But somehow I questioned whether that was true. I believed that success would not just fall from the sky without him holding a particular government office and having the courage to take action. Suppose an opportunity arose and you were in a position to do something that would promote Taiwan’s interest. Your decision to act or not to act would still depend on whether you took pride in being Taiwanese, having Taiwan’s best interest at heart, and having the courage to do something for Taiwan. Let’s take for example the success he had with getting the Japanese government to agree to shorten the visa approval process for visitors from Taiwan. This event took place while he was serving his post in Japan as a diplomat. When he started his job in Tokyo, visa applications for Taiwanese visitors to Japan took about two weeks. Mr. Chang discovered that there existed a discriminatory practice in Japanese government where the treatment for Taiwanese visitors was worse than that of Unequal Treaties. When Japanese visitors wanted to go to Taiwan, they needed only 24 hour for their visas to be issued, which was a far cry from the two weeks turn-around time required for their counterparts in Taiwan. The Japanese government cited the absence of official diplomatic channels between the two countries as the main reason for the lengthy processing. This was a lie because visa applications were processed entirely in the Japanese government’s office in Taipei. Furthermore, Taiwan officers traveling on government business could obtain visas to Japan much more quickly. But if you were an average citizen then you would have to get in line five o’clock in the morning and brace yourself for all kinds of hassle and red-tape. Chang Chao-Ing wanted to get off his chest the indignation he felt on behalf of all Taiwanese who wanted to travel to Japan. By chance he learned that under Japan Ministry of Foreign Affairs there was a consultation group called “Committee for Tourism Review”. From their pamphlets he discovered that one of the committee members Ms. Hashimoto was a well-known television producer. He asked his friend to set-up an appointment with her and began his lobbying efforts. He shared with Ms. Hashimoto some data from 1980 which showed that visitors from Taiwan accounted for more than five hundred thousand entries to Japan with an average spending of one million yen per visitor. This was equivalent to having a column of trucks carrying full loads of Japanese products ranging from electronic appliances to local souvenirs. On top of that, there were large numbers of Taiwanese students studying abroad in Japan. If a student were to get sick, should the parents wait for two weeks before they could visit their child? That would seem unreasonable. Ms. Hashimoto nodded her head as she listened carefully to Mr. Chang’s pleas. At the end of the meeting she verbally agreed to do something about it. She followed it up by taking money from her own pocket and invited the other committee members to discuss this matter over a meal. When all committee members were persuaded and a consensus reached, they called a formal committee meeting and summoned the officers from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to attend. Under pressure the Ministry of Foreign Affairs responded to the committee’s demands for change. Within two months of working, the visa turn-around time was shortened from two weeks to two days.

Chang Chao-Ing was born in Tokyo in 1933. His mother, Gang Bao-Tsai, passed away when he was nine months old. He became a precious darling of a grandson raised and cared for by his grandparents. During the period between 1936 and 1945, his father Chang Yuei-Chen was exiled and barred from returning to Taiwan for his anti-Japanese activities in Guangdong and Shanghai. Chang Chao-Ing entered Jieng-Cheng Elementary School in Taipei in 1939. In the following year he transferred to a Japanese elementary school in Shanghai where he was reunited with his father. Two years after that, war broke out and he was sent back to Taiwan where he attended Beitou Elementary School in Taipei. In 1945, he entered Taipei Second Middle School. In 1948 he went to Hong Kong and studied in Royden House School, an English language high school. In 1952 he entered Meiji University in Tokyo and studied politics and economics. After his graduation in 1956 he began his graduate studies at Sophia University. In 1957 He completed his graduate program and returned to Taiwan. In the following year he was employed by the Executive Yuen and worked in Group Three of the Department of Media and Broadcasting. It was from that position he began his career in the public sector. His career highlights included the following: l In 1963 the film he produced titled “Three Days in Formosa” won the silver prize in the Marseille Film Festival competition.l In 1967 he served as the officer in charge of media in the Taiwan Consulate in New York. l In 1980 he headed up the media department in Tokyo.l In 1985 he retired from his career in the government and left Tokyo. l In 1994 he returned to his old post in Tokyo and headed up the media group. He also served as a consultant to the Taiwan Consulate in Tokyo.l In 1998 he retired for the second time and returned to Taiwan.l From 2003 to 2007 he enjoyed his life in retirement.l In 2007 he passed away at the age of 74. During the span of his life he lived through the Japanese colonial period, the authoritarian rule of the KMT Party, the period of reform under President Lee Teng-Hui, and the current period of democracy in Taiwan. At each period of his life he excelled in the fights against oppression, totalitarianism, and injustice. By carrying on with such a strong conviction he surely had offended many people. Some called him a traitor to China. Others accused him of being a traitor to Taiwan. Some labeled him as a crony of the Song political circle. Some accused him of being a wasteful big spender. He treated those allegations with a nonchalant attitude. He took an impartial stance and worked diligently on what he thought was right during his thirty-one year career in government. He was keen to promote Taiwan’s interests and work hard to boost Taiwan prestige among the members of international community. He took on issues that would enhance freedom, democracy, and justice. The number of important international and domestic events he had participated in was too many to enumerate. Let’s just look at one such event that took place in 1975, a time period when persecutions against political prisoners were very harsh in Taiwan. This was right after the death of Chiang Kai-Shek and the power had fallen into the hands of his son Chiang Chin-Kuo. One day Chang Chao-Ing received a message from his cousin Lu Chen-Hui that one of the opposition leaders Hsieh Chung-Min was in imminent danger of losing his life. Hsieh Chung-Min together with Pang Min-Ming had published two articles: “Declaration of Formosan Self-salvation” and “CitiBank Bombing Incident”. He was imprisoned on two occasions for those declarations. When the news came out that he has fallen ill while in prison, many people in Taiwan and overseas sought to rescue him. Three individuals went to Amnesty International for help. They included Chang Chao-Ing’s wife Yen Chen-Her, Chang Tsang-Hong’s wife Chang Ting-Lan, and Lin Li-Chang of Commission Church. They wanted to speak to the Secretary General of Amnesty International but with such short notice they did not get a response. Chang Chao-Ing then made a phone call to Irene Payne, who was the secretary of James Buckley, a Senator from New York State. He asked Ms. Payne to meet with his wife Yen Chen-Her to talk about the plight of political prisoners in Taiwan. The meeting took place over lunch the next day and concluded with a message conveyed to Senator Buckley that urged him to inquire into the wellbeing of Hsieh Chung-Min with the authorities in Taiwan. Shortly after that meeting Senator Buckley wrote a letter to the Taiwan Embassy expressing concerns about the harsh treatment of political prisoners in Taiwan. The Senator’s secretary handled this matter with great care. She first sent a copy of that letter to Yen Chen-Her and then called Chang Chao-Ing informing him that the letter has been sent by certified mail and there was no need to worry. Hsieh Chung-Min was transferred from prison to the hospital in less than a week’s time. When Hsieh Chung-Min came out of prison he could not figure out who had petitioned for his release. He only knew that Alliance for Formosa Independence had released the news about his illness. It wasn’t until 2004 when Yen Chen-Her showed him the copy of the letter and other documents that he learned the inner workings of the rescue. One of the proudest things Chang Chao-Ing has done in his career was the fact that he never joined KMT. It was not an easy feat to serve as a senior officer in the government for thirty-one years without joining the Party. This was a testament to his uncanny ability to distance himself from KMT and his superb language abilities in English and Japanese that were highly sought after by those in power. There is an age-old debate on whether a hero is the one who defines the times or is defined by the times. Taiwan was in a very weak position in international relations when Chang Chao-Ing served his posts in Japan and the U.S. He was able to overcome obstacles in the diplomatic front with his wisdom and skills. He established a stage for Taiwan to be seen and heard by building good relationships with the members of broadcasting community and news agencies. I believe that without having the right skill sets you could not seize the opportunity and take effective action no matter how motivated you were by your ideals. One may argue that Chang Chao-Ing was born with conditions favorable to his success and he did not have to work hard for it. On the subject of working hard, I would like to point out one passage in the book that described how dedicated he was in learning the English language. In 1948 at age fourteen and enrolled in Royden House School, a British institution, he had three tutors– one to teach him Chinese and two to teach him English. Still feeling inadequate, he ran newspaper ads and hired another English tutor. This tutor also taught him about democracy, the freedom of speech, the freedom of press, and told many tales of the great American thinker Thomas Jefferson. At one point in time, Chang Chao-Ing had aspirations of becoming a journalist because of those teachings. In fact, he recalled that Mrs. Margaret Hampson was one of the most influential people in his life, one who had shaped his career choices. When he entered Meiji University in Japan to study politics and economics, Chang Chao-Ing continued to strive for excellence in English by taking a night course in English Rhetoric at Sophia University. From these accounts we can get a glimpse on how hard he had worked on equipping himself. Speaking of Sophia University, there was a side story there that Chang Chao-Ing would never forget. While a student at Sophia University, on one weekend he was invited by a judge from the Japanese High Court to attend a party. The purpose of the party was to select a wife for Prince Akihito. A woman he danced with that night, Michiko, turned out to be the woman who eventually became the wife of Prince Akihito. I believe this story would arouse the curiosity of readers who may want to learn more about the fascinating things that took place in Chang Chao-Ing’s colorful life.